Chronicling America Digitized Newspapers

Project Timeline

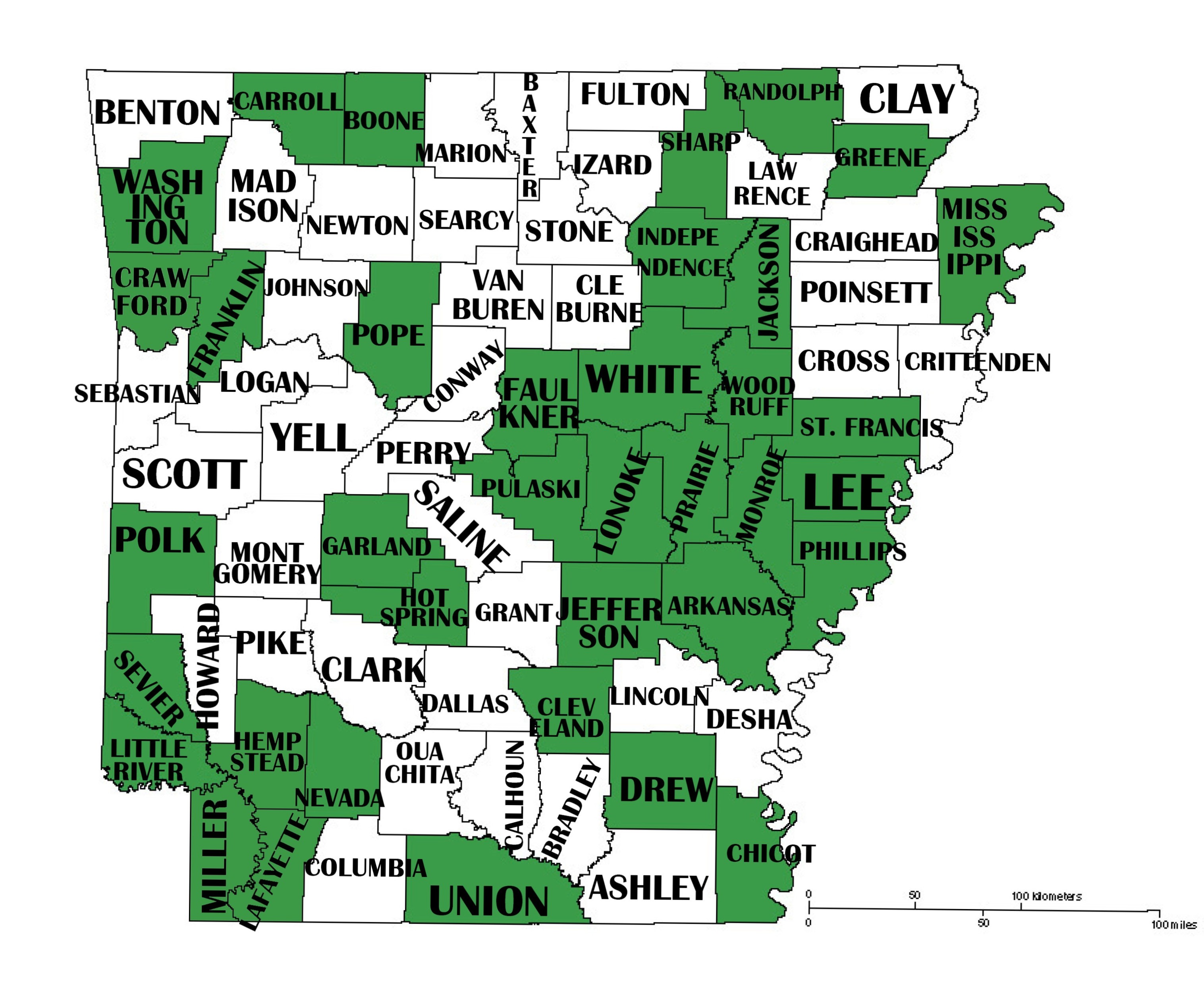

In 2017, ASA was awarded a two-year grant (2017-2019) to select, duplicate, and digitize historic Arkansas newspapers with a goal of producing 100,000 pages of content for the Chronicling America website. By the end of the first cycle, ASA had digitized 100,630 pages from 40 newspaper titles representing 15 counties in the state.

In 2019, ASA was once again awarded a second two-year grant (2019-2021) which added an additional 20 newspaper titles representing 13 Arkansas counties for a total of 199,299 pages added to the Chronicling America website.

In 2021, ASA was awarded a third grant (2021-2023) to fund an additional 100,000 pages of content. The emphasis on newspaper title selection for this cycle is focused on underrepresented communities including female-owned and operated papers, minority-owned papers, and foreign language papers.

In August, 2023 ASA was awarded funding for an additional cycle of the grant. This cycle will begin on September 1, 2023 and end August 31, 2025. In this cycle the team will focus on newspaper titles that demonstrate the evolving relationship between the economy and the environment, from Arkansas's territorial period from 1819 to the mid-1930s.

The newest titles added to Chronicling America include Woman's Chronicle, Arkansas Ladies' Journal, Little Rock Ladies' Journal, Rural and Workman and "Ladies Little Rock Journal", Southern Ladies' Journal, Arkansas State Press, Arkansas Echo, Stuttgart Germania and the De Queen Bee.

The Team

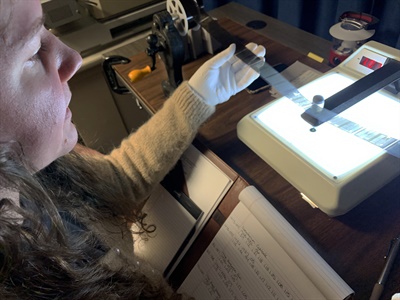

The ADNP team is made up of seven ASA archivists and microfilm technicians, with two staff members being dedicated to the project full-time. In addition to ASA staff, the digitization and duplication process is outsourced to a third party vendor. Additionally, ASA staff works with an advisory committee to give guidance and expertise when selecting the titles to include in the project each cycle.

- Dr. Guy Lancaster, Editor for CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas, Central Arkansas Library System. Dr. Lancaster earned his PH.D. in Heritage Studies from Arkansas State University and has taught and written about Arkansas history. Since 2005 he has edited the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas, a project of the Central Arkansas Library System.

- Dr. Kimberly Little, Lecturer, University of Central Arkansas. Dr. Little earned her bachelor’s degree with honors at Harvard and her M.A. and Ph.D. at the University of Wisconsin. Her academic focus is teaching, but her research interests lay primarily in environmental and urban history. She is a specialist of research methods and twentieth-century America. She teaches environmental history, research methods, and US surveys and has taught public history.

- Dr. Sharon Silzell, Associate Professor of History, University of Arkansas at Monticello. She earned her Ph.D. from the University of Texas in Austin in 2015. Dr. Silzell is the president of the Arkansas Association of College History Teachers (AACHT), the regional coordinator for National History Day in Southeast Arkansas, and co-faculty advisor for Phi Alpha Theta (an academic honors society for history students). Her affiliations demonstrate that she is familiar with history outreach and coordination, and she will be a valuable partner in spreading awareness of Chronicling America and its uses for history research.

- Dr. Jeannie Whayne, Professor of History, University of Arkansas. Dr. Whayne is a specialist in agricultural and southern history. Her research focuses on the lower Mississippi River Valley and the interplay of social and economic history with environmental change, agricultural development, and race relations.

- Joshua Youngblood, Instruction and Outreach Unit Head for the Special Collections Division in the University of Arkansas Libraries. Mr. Youngblood serves as the history and rare books librarian and the curator of the Arkansas Collection. Before joining Special Collections in 2011, he was a member of the Florida Memory Project of the State Archives of Florida, served as the information office of the Florida Division of Cultural Affairs and was a staff member of Florida Main Street in the Bureau of Historic Preservation. He has published on digital archival exhibiting and archival instruction programs, as well as on the history of Arkansas, lynching, and reform movements in the American South. A graduate of Florida State University, Youngblood is a certified archivist and a past president of the Society of Southwest Archivists.

Education Resources

The ADNP team has several resources you can print and use in your classrooms or libraries.

Promotional Materials:

Research Guides and Resources:

- Comprehensive Guide - 8-page comprehensive guide to researching Chronicling America

- Quick Guide - 1-page tips and tricks to researching Chronicling America

- Genealogy Guide - 4-page genealogy-specific research guide to Chronicling America

- Cemetery Guide - 1-page cemetery-specific research guide to Chronicling America

- Non-NDNP Free Online Newspapers - Comprehensive list of all Arkansas newspapers that are available for free online

- What is a Newspaper - 2-page guide introducing upper-level high school and college students to a brief history of newspapers and commonly used terminology.

- Parts of a Newspaper - 8-page color guide giving an in-depth overview of the common parts of a newspaper (i.e. masthead, byline, publisher's block, etc.)

- Diagram of a Newspaper - a 6-page illustrative guide that diagrams the parts of a newspaper.

- What is a Newspaper guide for middle school researchers - 2-page guide introducing younger students (6th-9th grade) to the history and terminology of newspapers.

- Parts of a Newspaper guide for middle school researchers - 6-page guide defining the parts of a newspaper.

- Three-Step Quick guide - 1-page color guide designed to get students started on Chronicling America.

Topic Guides:

The Arkansas Digital Newspaper Project team has created Arkansas-specific topic guides for popular research topics in Chronicling America. Guides include a history of the topic, common search terms, selected newspaper articles, timeline of significant dates and additional educational resources and lesson plans. New topic guides will be added regularly.

Land and Resources

Apple Industry in Arkansas - Apples were the dominant crop in Northwestern Arkansas in the late 1800s and early

1900s. The apple industry had a significant impact not only in the Northwest but on the entire state, so much so that in 1901 the apple blossom was chosen as the state flower. By the 1930s, however, multiple factors contributed to the decline of Arkansas'

apple industry and the apple boom was over.

Pearl Rush and Mother-of-Pearl Button Industry in Arkansas - Arkansas' rivers and lakes are home to many species of freshwater mollusks that produce pearls. Native Americans were the first to collect pearls in what would later become Arkansas. As European settlers pushed Native Americans out of Arkansas Territory, mussels were largely left alone, and pearls built up for years without being harvested. Eventually the new inhabitants realized that Arkansas' mollusks created valuable pearls, and in the late 1800s the pearl craze began.

Timber Industry in Arkansas- Arkansas’s abundant forests presented obstacles and opportunity for early European settlers. Clearing trees for settlements and farms by axe and saw was slow and laborious, but yielded the raw lumber needed for houses, barns, fences, and furniture. Advances in technology were used to improve timber processing, and by the 1850s steam powered sawmills were common across Arkansas. Despite the increase in output with advancing mechanization, these sawmills could only serve nearby communities because they lacked practical long-distance transportation. This changed after the Civil War, when railroads were built across Arkansas. In the late 1800s, timber companies began using trains to expand their operations and export lumber state and nationwide.

Black Arkansans

Black Arkansans in the Military Until Desegregation - The first all-Black military units in Arkansas were formed in 1863 during the Civil War. Though Black Arkansans were allowed to join the military, they were typically given inferior jobs and segregated from white troops. Black troops were expected to perform at the same level as white troops while facing unfair and unequal treatment. Despite this inequality, Black divisions were an important part of the U.S. military until its desegregation after World War II.

Race Riots in Arkansas - Racial tension in Arkansas was high at the end of the Civil War. Though the

South had been defeated and slavery was abolished, the lingering effects of slavery and racism continued. The changing economy and polarizing political climate caused social unrest, which turned into racial violence targeted at Black Arkansans. The first race riots and race wars in Arkansas followed soon after.

Slavery in Arkansas - The first report of enslaved Black people in Arkansas Territory came from French colonists in the early 1700s. Slavery was a major part of the early economic development in Arkansas, with significant slave labor occurring on large plantations throughout the state. The use of forced labor allowed for the rapid expansion of cotton farming, which added close to $16 million to the Arkansas economy each year. By 1860 the state was the sixth largest producer of cotton, and 25% of Arkansas' population was enslaved.

Transportation

Railroad Strikes in Arkansas - An industrialization increased across the U.S. in the late 1800s and early 1900s, so did efforts to inprove working conditions and pay. Workers formed unions, banding together to negotiate with their employers. Railroad workers were some of the first laborers in Arkansas to unionize. Labor strikes, that is withholding labor, were one of the tactics used by employees and unions during negotiations for better treatment. Strikes often turned dangerous, as workers resorted to sabotage and clashed with company men, law officers and government militia. During the railroad's Golden Age at the turn of the 20th century, there were many minor and two major railroad strikes in Arkansas.

Military & Wartime

Railroads in the Civil War - The Memphis and Little Rock (M&LR) was the only working railroad in Arkansas when the Civil War began in 1861. It was still under construction, but the company planned to connect central Arkansas at Huntersville (now North Little Rock), on the Arkansas River, to the eastern edge of Arkansas at Hopefield, across the Mississippi River from Memphis, Tennessee. This rout would link the central Arkansas to the major Memphis port. The M&LR continued construction during the first few years of the Civil War, but progress eventually came to a standstill. The M&LR was commandeered by Union and Confederate Armies over the course of the war.

Digitized Newspapers

Below is the complete list of Arkansas newspaper titles that have been digitized along with information about each of the newspapers. To view digitized issues and begin your research visit chroniclingamerica.loc.gov.

Little Rock is the Pulaski County seat and state capital in central Arkansas. In 1863, during the Civil War, the city fell to Union forces, and the Confederate capital moved to Washington, Arkansas. Arkansas's capital returned to Little Rock at the end of the war in 1865. That same year the city hosted the Convention of Colored Citizens, a meeting of Black residents who strived for more civil rights after emancipation, including suffrage and education. This was the first of many Black operated businesses and associations opening in Little Rock during Reconstruction. Arkansas's first governor elected during Reconstruction was Powell Clayton, a Union general who moved to Arkansas after the war.

John E. Bush was born enslaved in Moscow, Tennessee in 1856. As Federal soldiers advanced through Tennessee at the end of the Civil War, Bush's enslaver fled the state, taking Bush and his mother with him to Arkansas. After emancipation, Bush settled in Little Rock. He graduated from Little Rock High School with honors in 1876. In the 1880s, he entered politics, rising to the position of secretary of the Pulaski County Republican Party in 1892. In the factious Republican Party, he was loyal to former governor and senator Powell Clayton. In 1883, John E. Bush and businessperson Chester W. Keatts, concerned about the lack of affordable insurance for Black Americans, founded a fraternal organization designed to provide insurance for members of the Black community. They named the organization the Mosaic Templars of America. Soon, there were chapters across the country, with the headquarters in Little Rock.

Needing a way to promote the organization, Bush started the American Guide newspaper in 1885. This newspaper was published on Little Rock's Ninth Street, a business district that catered to a largely Black clientele. In addition to covering the activities of the organization, Bush's paper advocated for the Republican Party. He appointed David G. Hill to serve as editor of the paper. A weekly paper, it struggled to stay in business. Bush closed the paper from 1886 to 1888. He reopened the paper in 1889, printing the reopening date on the newspaper's masthead as the establishment date, despite the earlier publications. In 1896, the Guide promoted ad space to potential advertisers by printing a note that it had a city circulation "equal to that of any weekly paper published in Little Rock and has double that of any Negro paper published in the city."

In 1898, President Benjamin Harrison appointed Bush to the position of Receiver of the General Land Office. With new responsibilities, Bush had little time to run his newspaper and he sold it to W.A. Singfield, with David G. Hill continuing as editor. By 1904, Singfield renamed the paper the Mosaic Guide (18??-19??) to reflect its purpose as the official organ of the Mosaic Templars of America. The newspaper continued until the 1930s when the Little Rock headquarters of the Mosaic Templars of America closed.

As of this writing, there are few surviving issues of the Guide. This is the case for many Black newspapers, as past archival organizations were often neglectful of preserving the Black community’s written heritage, and the newspapers did not survive. When newspapers disappear, Black voices are forever lost, leaving a large gap in the understanding of our history.

For more information about this title, visit https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83025496/.

Little Rock is the center of Arkansas geographically as well as politically, serving as the state capital and county seat of Pulaski County. It is on the southern side of the Arkansas River and extends to the foothills of the Ozark Plateau, the Delta leading to the Mississippi River, and the plains stretching into Texas. In 1821, the territorial capital moved to Little Rock from Arkansas Post. Little Rock was incorporated in 1831 as a town in Arkansas Territory and incorporated as a city in 1835. The next year, Arkansas became the 25th state in the United States with Little Rock as the capital.

The Arkansas Advocate was the second paper published in Arkansas Territory, beginning in Little Rock in March 1830. Charles Pierre Bertrand was the founder and editor of the paper, which he published weekly. Robert Crittenden, first Territorial Secretary and acting Governor, contributed many articles to The Arkansas Advocate. A month after starting the Advocate, Bertrand married Crittenden's sister-in-law and they later named their son after Robert Crittenden.

Bertrand studied law under Crittenden and went on to hold several political offices, including State Treasurer, member of the House of Representatives, and Little Rock Mayor. Bertrand opposed secession from the United States and some historians credit him with delaying the start of the Civil War by dissuading Arkansans from attacking the Federal Arsenal in Little Rock.

Bertrand intended for the Advocate to be politically and religiously neutral, but in actual practice, it supported the politics of the editors. Early Advocate issues backed the Republican party, which soon became the National Republication party and then the Whig party. It was the first paper to suggest Arkansas become a state, as Benjamin Desha wrote an article supporting statehood in 1831. Democrats at the time opposed statehood, concerned that taxes would be too high for the small Arkansas population.

At first, Bertrand was friendly with the Democratic The Arkansas Gazette (1819-1836), the first newspaper in Arkansas. Bertrand previously worked for William Edward Woodruff, the paper's founder and editor. However, in 1830, Woodruff published an editorial from someone using the name "Jaw-Bone" that maligned Bertrand, after which the newspapers were hostile and published pointed articles about the other newspapers' editors.

Albert Pike wrote letters for the Advocate, and Bertrand sent prominent Whigs Crittenden and Jesse Turner to bring him to Little Rock to work at the Advocate. Pike became associate editor and in 1835 purchased the paper from Bertrand. Pike used the Advocate to promote Whig Party politics.

Charles E. Rice and Archibald Coulter ran the paper for several years under Pike. Coulter became Pike's partner in 1837. That same year, the Advocate merged with The Arkansas Weekly Times (1836-1837) to become the Arkansas Times and Advocate (1837-1844). After the merger, John Reed ran the newspaper with Pike contributing some articles.

After changing ownership and politics multiple times over the years, including a brief stint as a Democratic newspaper, the Times and Advocate was discontinued in 1844.

For more information about this title, visit https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn87062070/.

Little Rock, in central Arkansas, is the county seat of Pulaski County and the capital city. Pulaski County, one of the first five counties in Arkansas, was established in 1818. The county includes the Ouachita Mountains, Mississippi Alluvial Plain, and Coastal Plain. Little Rock was incorporated as a city in 1835 and was a hub of activity early in the state's history. Construction on the statehouse building began in 1833 along the banks of the Arkansas River. Both the county government and state government worked in the statehouse until 1883.

In 1843, Democrats in Little Rock needed a new newspaper, as the Arkansas State Gazette (1836-1850) shifted its affiliation from Democratic to Whig after an ownership change. The Arkansas Banner was founded by Archibald Yell in 1843 to be the voice of the Democrats, under the publishing name the Democratic Central Committee of the State of Arkansas. Dr. Solon Borland worked as editor with Elbert Hartwell English, who was also his associate at their joint law firm. Borland had writing experience from working at several newspapers in Memphis, Tennessee. The Banner soon changed publisher names to Borland & Farley, with Borland still working as editor.

Borland quickly began writing pointed articles about the Gazette editor, Benjamin John Borden. These jabs led to physical fights and finally a pistol duel between the two. Borland won the duel by shooting Borden. Since Borland was a doctor, he proceeded to patch Borden's gunshot wound. This led to a great friendship between the two.

Borland worked at the Banner until the start of the Mexican American War in 1845, at which time he was elected major of the Arkansas Mounted Infantry Regiment and left for Mexico.

Archibald Hamilton Rutherford took charge of the Banner next, and he ran it until 1846. Since the Banner was the voice of the Democrats, Rutherford was carefully chosen by the Democratic Party to run the paper. He had been a county judge in Clark County and clerk of the circuit court. Later he was elected to the Arkansas State Legislature for several terms and appointed deputy clerk of the United States court at Little Rock.

After Rutherford left in 1846, Lambert Jeffrey Reardon took over. He hired Lambert A. Whitely as junior editor. Reardon and Whitely were also involved in editorial and physical fights over personal insults with other newspaper editors. In one such physical fight, Borland, one of the previous Banner editors, happened to be passing by and joined in to prevent Reardon from shooting his opponent. Apparently, Borland did not want that fight to have the same outcome as his own newspaper duel.

Whitely eventually took control of the Banner, and in 1851 he added "Democratic" to the masthead, creating the Arkansas Democratic Banner. The next year he sold the paper and the name changed to The True Democrat (1852-1857) under publishers Richard Henry Johnson and Reuben S. Yerkes.

For more information about this title, visit https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82007022/.Little Rock, in central Arkansas, is the county seat of Pulaski County and the capital city. Pulaski County, one of the first five counties in Arkansas, was established in 1818. The county includes the Ouachita Mountains, Mississippi Alluvial Plain, and Coastal Plain. Little Rock was incorporated as a city in 1835 and was a hub of activity early in the state's history. Construction on the statehouse building began in 1833 along the banks of the Arkansas River. Both the county government and state government worked in the statehouse until 1883.

In 1843, Democrats in Little Rock needed a new newspaper, as the Arkansas State Gazette (1836-1850) shifted its affiliation from Democratic to Whig after an ownership change. The Arkansas Banner was founded by Archibald Yell in 1843 to be the voice of the Democrats, under the publishing name the Democratic Central Committee of the State of Arkansas. Dr. Solon Borland worked as editor with Elbert Hartwell English, who was also his associate at their joint law firm. Borland had writing experience from working at several newspapers in Memphis, Tennessee. The Banner soon changed publisher names to Borland & Farley, with Borland still working as editor.

Borland quickly began writing pointed articles about the Gazette editor, Benjamin John Borden. These jabs led to physical fights and finally a pistol duel between the two. Borland won the duel by shooting Borden. Since Borland was a doctor, he proceeded to patch Borden's gunshot wound. This led to a great friendship between the two.

Borland worked at the Banner until the start of the Mexican American War in 1845, at which time he was elected major of the Arkansas Mounted Infantry Regiment and left for Mexico.

Archibald Hamilton Rutherford took charge of the Banner next, and he ran it until 1846. Since the Banner was the voice of the Democrats, Rutherford was carefully chosen by the Democratic Party to run the paper. He had been a county judge in Clark County and clerk of the circuit court. Later he was elected to the Arkansas State Legislature for several terms and appointed deputy clerk of the United States court at Little Rock.

After Rutherford left in 1846, Lambert Jeffrey Reardon took over. He hired Lambert A. Whitely as junior editor. Reardon and Whitely were also involved in editorial and physical fights over personal insults with other newspaper editors. In one such physical fight, Borland, one of the previous Banner editors, happened to be passing by and joined in to prevent Reardon from shooting his opponent. Apparently, Borland did not want that fight to have the same outcome as his own newspaper duel.

Whitely eventually took control of the Banner, and in 1851 he added "Democratic" to the masthead, creating the Arkansas Democratic Banner. The next year he sold the paper and the name changed to The True Democrat (1852-1857) under publishers Richard Henry Johnson and Reuben S. Yerkes.

For more information about this title, visit https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82007020/.The Arkansas Echo, an all-German language newspaper, began publication in 1891. It was published in Little Rock under the Arkansas Echo Publishing Company, composed of John Kaufman, Adolph Arnold, Andrew Rust, Father Bonaventure Binzegger, Friedrich "Fred" Hohenschutz, Herman Lensing, Charles "Carl" Meurer, J. P. Moser, and Nic Peay. The Echo publishers purchased an existing newspaper plant from Der Logan County Anzeiger (Logan County Gazette), run by Conrad Elsken in Paris, Arkansas. At the time of purchase, the Anzeiger had a circulation of 400 in Logan County, but on the direction of a Catholic priest in Little Rock, the newspaper plant was moved to Little Rock to reach a wider audience. In Little Rock, the paper was renamed the Arkansas Echo and the Anzeiger's subscribers were shifted over. The Echo was a Democratic, eight-page paper, originally published on Fridays with a circulation of 850 subscribers. Over the years, the paper grew to 1,300 subscribers.

The Echo had an unsteady start as their inaugural issue was sabotaged. Before the papers could be printed, someone broke into the Echo's newspaper office and destroyed the forms laid out for printing. Instead of their planned eight-page issue, the Echo's first issue was a half-sheet page on December 31, 1891. In that issue, the Echo blamed the sabotage on Philip Dietzgen, editor of the other German newspaper in Little Rock, the Arkansas Staats-Zeitung (1869-1917). The Echo related to its readers that the saboteur had cut themselves when destroying the Echo's office and left a trail of blood drops to the Zeitung's office. This event spurred a year-long newspaper war involving fistfights, threats, and lawsuits, making national news. The impetus for the rivalry seemed to be competition for German customers, as the Staats-Zeitung had been publishing in Little Rock since 1869.

In spite of anti-German sentiments during World War I, the Echo persisted in publishing the news for German readers in Arkansas. Unlike other German newspapers across the U.S., the Echo survived and continued printing in German, even as many German businesses shifted away from avowing their German heritage.

The driving force behind the Echo was Carl Meurer, a German Catholic who immigrated in 1881. By 1892, he was the sole editor of the paper. Meurer worked at the Echo until he died in the newspaper office in 1930. Meurer's headstone is inscribed: "His life's work: editor of 'Arkansas Echo.' Motto 'For truth and justice will be remembered throughout the years.'"

After Meurer's death, the Echo Publishing Co. appointed Meurer's son, Carl J. Meurer, Jr., as his successor. Despite staying in the family, the Echo ceased publication just two years later.

For more information about this title, visit https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn88084068/.

Little Rock is the center of Arkansas both geographically and politically. It hosts the state capitol and Pulaski County seat along the south bank of the Arkansas River. The capital briefly withdrew from the city during the Civil War, but Little Rock quickly regained the governing seat after the war. Despite the resolution of the war, the political and social turmoil continued in the late 1800s during Reconstruction. Black Arkansans struggled to gain a foothold in society after the abolition of slavery. In 1868, Arkansas was the first Confederate state to allow Black men to vote. This contributed to the tumultuous political scene, as white voters worked to prevent Black men from utilizing their newly acquired voting rights.

Arkansas's first Black newspaper, the Arkansas Freeman began publication in 1869 amid this political instability. Leading up to the founding of the Freeman, Reconstruction policies enacted by U.S. Congress caused major political changes in Arkansas. These policies resulted in the political disenfranchisement of former Confederate officials and allowed Black men to vote. In 1868, new leadership was brought to the state, and Powell Clayton, a Pennsylvania Civil War soldier, was elected governor of Arkansas. A wave of political violence followed as former Confederates and the Ku Klux Klan tried to intimidate Black Republican voters from exercising their political rights. Nevertheless, by 1869, the political turmoil halted after Clayton declared martial law and organized state militias to stem the violence. The Morning Republican (1868-1872), a white owned newspaper and mouthpiece of the Powell regime, was widely read by Republicans throughout the state.

However, factions developed within the Republican Party as the turmoil of 1868 began to die down. One of the fissures was between white Republicans and Black Republicans. Even though former enslaved men in Arkansas made up a large percentage of the Republican vote in Arkansas, there were no state-wide Black officeholders and no Black-owned newspaper. In June 1869, a group of Black businesspeople and clergy met at City Hall in Little Rock to discuss opening their own newspaper to fill the gap. At first, the owners of the Morning Republican applauded the move. The Weekly Arkansas Gazette (1866-19??) joined in the acclaim, writing that it hoped that the new paper would separate Black voters from their devotion to the Powell administration. The organizers named the paper the Arkansas Freeman, designating it the first Black-owned newspaper in Arkansas.

The Freeman founders chose Tabbs Gross, a formerly enslaved man and later minister from Kentucky, newly arrived in Arkansas, to run the new newspaper. Gross purchased his freedom before the Civil War and traveled to Ohio to assist the efforts in freeing enslaved people via the Underground Railroad. After the war, he settled in Arkansas, working to assist newly freed men gain their political rights. He felt that Arkansas's Black population had little voice within the Radical faction of the Republican Party.

The paper launched in August of 1869 under Gross's declaration that it supported an end to disenfranchisement of former Confederates, universal male suffrage, and amnesty for Confederates. These issues were at odds with the Clayton administration. Soon, a war of words erupted between the Arkansas Freeman and the Morning Republican. In the first issue of the paper, Gross declared that the Arkansas Freeman stood for an end to disenfranchisement of Southern whites, "who are unjustly deprived of many of the rights and privileges we enjoy." Additionally, he advised Black voters should end their "blind loyalty" to the Radical position and forge a new path based on political rights for all Arkansans. Further, he emphasized that Black citizens in Little Rock made up 90 percent of the party, yet Black Republicans held no offices in city government. In response, editors of the Morning Republican replied that Gross was a traitor. His political standing with the Republican Party began to fail. As a result, readership declined and the paper closed in the summer of 1870, after less than a year of publication.

As of this writing, there are only a few surviving issues of the Freeman. This is the case for many Black newspapers, as past archival organizations were often neglectful of preserving the Black community’s written heritage, and the newspapers did not survive. When newspapers disappear, Black voices are forever lost, leaving a large gap in the understanding of our history.

For more information about this title, visit https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83025492/.

In January 1842, Francis M. Van Horne and Thomas Sterne moved to Van Buren, the Crawford County seat, and founded the Arkansas Intelligencer. Van Buren was close to Indian Territory (Oklahoma), just five miles from the border, near Fort Smith in Northwest Arkansas. The Intelligencer was the first newspaper in Arkansas west of Little Rock. The editors boasted that the paper would "go East from a point farther West than was ever paper printed in the United States." Van Horne and Sterne wrote that their paper was politically neutral, with the slogan "let every freeman speak his thoughts." The Intelligencer was published every Saturday. It included advertisements from steamboats traveling the Arkansas River that stopped at Van Buren on their way to New Orleans, Louisiana and Cincinnati, Ohio. Despite the port in town, river travel was uncertain in the mid-1800s, and some of the Intelligencer issues were published on small sheets of paper with an editor note that they had not yet received their shipment of newsprint.

Before Van Horne and Sterne founded the Intelligencer, they lived in Little Rock where they were involved in several types of printing jobs. In 1839, Little Rock businessperson and gang leader Samuel G. Trowbridge directed his gang to create counterfeit bank notes. He hired Van Horne, who worked at the Arkansas State Gazette (1836-1850), to print the notes. In 1841, Trowbridge again had Van Horne create counterfeit notes. At that time, Van Horne worked at the Arkansas Times and Advocate (1837-1844), where he stole pieces of type from the newspaper office to print the banknotes. Sterne, another printer in the Trowbridge gang, also helped produce the notes. The following year, Van Horne and Sterne moved to Van Buren to begin their paper.

Back in Little Rock, Trowbridge became the mayor in May 1842. Soon after taking office, Trowbridge's wife was caught using stolen bank notes. This led to the arrest of Trowbridge, Van Horne, and other gang members for their involvement in the criminal activities. After serving only 8 months as mayor, Trowbridge left office to serve jailtime, where he earned a reduced sentence of five years in exchange for providing information on gang members and the location of the counterfeiting equipment. Van Horne was sentenced to six and a half years in the state penitentiary.

Sterne avoided jailtime and continued working at the Intelligencer. In 1842, he hired John Foster Wheeler to replace Van Horne as editor. Wheeler previously worked in Georgia, where he was the printer for the first Native American newspaper in a native language, the Cherokee Phoenix (1828-1829). From there, Wheeler moved to Indian Territory, where he printed many works in Cherokee, Creek, and Choctaw. Wheeler left Indian Territory after encountering tribal infighting and moved to Van Buren where he joined the Intelligencer. The Intelligencer included news segments from Indian Territory, which had no newspapers at the time. Wheeler left the Intelligencer in 1843 and returned to Indian Territory and resumed printing works in Native languages. He eventually settled in Fort Smith, where he founded the first newspaper in the city, the Fort Smith Herald (1847-18??).

In 1843, George Washington Clarke joined the Intelligencer. In 1844, Sterne left, and Clarke assumed control, changing the Intelligencer from neutral to Democratic. This incited Sterne to begin a rival newspaper, the Western Frontier Whig (1844-1846), and hire John S. Logan as editor. What followed were "warm controversies" between the two papers stemming from the editors' political rivalry and opposing personalities. Clarke was described as brilliant, but impulsive and forceful. After the men turned to personal insults, with Clark calling Logan "Big Mush," who returned the insult with "Toady Clarke," they agreed to duel. In 1844, Logan and Clarke held their rifle duel in Indian Territory. At 60 paces they fired and missed their marks, and the "smell of powder and bad marksmanship led to reconciliation." In 1845, the Intelligencer included the following caveat for ads they would allow: "No advertisements of a gross, abusive, personal nature, will be published at any price." Later that year Clarke left the Intelligencer, and the following year the Whig folded.

From 1845 to 1847, Josiah Woodward Washbourne and Cornelius David Pryor ran the Intelligencer. Washbourne was the older brother of Edward Payson Washbourne, who created the famous Arkansas Traveler painting around 1855.

In 1847, Clarke returned to the Intelligencer and ran it alone until 1853. His issues had strong guest contributors, including one writing under the name "Clementine," who was said to be a 13-year-old girl living in Fayetteville. During this time Clarke served in the Arkansas House and Senate. In 1853, he left the Intelligencer for the final time, along with his position as Senator, after being appointed Indian Agent for the Pottawatomie Indians in Kansas Territory. Once there, Clarke became notorious during the Bleeding Kansas era as a ruthless proslavery leader. After the Civil War ended, Clarke moved to Mexico City, Mexico where he started the Dos Republicas ("Two Republics") newspaper.

Anslem Clarke, George Clarke's brother, took over the Intelligencer in 1853 when George left. He was described as a "frank, sincere, warm-hearted man" and a "brilliant writer." Anslem ran the paper until his death in 1859, and the Intelligencer folded. The Intelligencer newspaper plant was purchased by William Henry Mayers and moved to Fort Smith, where he used it to start the Democratic Thirty-Fifth Parallel (1859-1861), which ran until the Civil War.

For more information about this title, visit https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82016488/.

In late-nineteenth-century Arkansas, women's voting rights gained traction as one of the leading political issues. Little Rock quickly became the hub of the state's suffrage movement, since it was the state capital and Pulaski County seat, making it the center of the state both politically and geographically. The first major publication to advocate for women's suffrage in Arkansas was the Ladies' Little Rock Journal, started by Mary Ann Webster Loughborough in 1884. The Journal was also the first Arkansas newspaper started by a woman and written for a female audience.

Before launching her newspaper, Mary Ann Loughborough had published a popular book of her first-hand experience at the siege of Vicksburg, Mississippi, during the Civil War. Her husband, James Moore Loughborough, served as a major in the Confederate Army, and Mary Ann and their daughter Jean moved with him to his various duty stations. Mary Ann kept a diary during the Vicksburg siege, which she later turned into the book My Cave Life in Vicksburg, published in 1864. After the Civil War, the Loughboroughs moved to Little Rock, where James died in 1876.

In 1884 Mary Ann Loughborough launched her newspaper, first publishing the Ladies' Little Rock Journal as part of another local newspaper, the Rural and Workman (1884-1???), a paper for farmers, mechanics, and workmen. By August 1884, she moved to publishing the Journal as a stand-alone paper, rearranging the title to the Little Rock Ladies' Journal. The Journal was a lengthy publication, typically running at 12 or more pages, issued every Saturday. Loughborough had several women writing for the paper, including her daughter, Jean Moore Loughborough, and Ellen Maria Harrell Cantrell. The Journal was unique among newspapers in the South for focusing not only on women's concerns, but also advocating for political issues like women's suffrage at a time when many were against women's voting rights.

The Journal's name changes over the years reflected its growth and increased reach, progressing from the Ladies' Little Rock Journal to the Little Rock Ladies' Journal to the Arkansas Ladies' Journal, and finally the Southern Ladies' Journal. Along with the expanded coverage indicated by the name change to the Southern Ladies' Journal in 1886, Loughborough planned to expand the paper itself by increasing the number of pages while publishing it twice a month rather than every week. However, the Journal's run ended unexpectedly in 1887 after her sudden illness and death.

Despite its early end, Loughborough's newspaper inspired the opening of the Woman's Chronicle (1888-1???), the next year. Catherine Campbell Cuningham, Mary Burt Brooks, and Haryot Holt Cahoon created the Chronicle to continue Loughborough's work for the women of the state. In its inaugural issue, it reported that the Journal had died with Loughborough, and they hoped to fill the void left behind so that the "daughters of Arkansas … should have and take pride in a paper all their own." The Chronicle, like the Journal, was a strong supporter of women's suffrage. Unfortunately, like the Southern Ladies' Journal, the Chronicle lasted less than five years before it ceased publication due to Cuningham's ill health.

For more information about this title, visit https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn90050096/.

In the 1950s, Little Rock, the capital of Arkansas, became the center of national attention during a desegregation crisis at Central High School. The events were covered extensively by the Arkansas State Press, a local newspaper started in 1941 by a Black civil rights activist couple, Lucius Christopher Bates and Daisy Lee Gatson Bates.

In 1941, the Bateses purchased the newspaper plant from the Twin City Press (193?-1940) [LCCN: sn92050007], a paper in Little Rock that had served the Black community in that city, Pulaski County, and Pine Bluff in Jefferson County. The Bateses renamed the paper the Arkansas State Press. Lucius Bates was the editor and manager, Daisy Bates worked as co-publisher, and Earl Davy served as photographer. The Press was an 8-page paper published every week on Thursday. It circulated in Little Rock and other Arkansas towns with significant Black populations, including Pine Bluff, Hot Springs, Helena, Forrest City, Jonesboro, and Texarkana. It was the largest Black newspaper in Arkansas during its run. The Press was unique, even among Black newspapers, in its strong campaign for civil rights. The paper endorsed political policies and candidates who worked toward equality in Arkansas. It also highlighted the achievements of Black Arkansans, along with social, religious, political, and sports news relevant to the Black community.

One of the major racially motivated events covered by the Press was the murder of a Black soldier by a white soldier in 1942 on the same street as the Press's newspaper office. This incident, which was underreported elsewhere, boosted distribution of the Press and earned it a reputation as the source for Black civil rights news and a voice for change. Another major cause during the paper's run was the desegregation of public schools, and the Press was the only paper in Arkansas to push for integration. For years the Bateses, who served as leaders in the Little Rock branch of the NAACP, pushed for racial integration in public schools despite pushback from white Arkansans and many Black Arkansans. In 1954, the Press celebrated the decision of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas to end segregation in schools. To put the law into action, Daisy mentored the Little Rock Nine, the first Black students to integrate into the formerly white Central High School in 1957.

The backlash from protestors of desegregation ended the Press's 8-year run. Though the paper had support from many in the Black community, its progressive views had long upset white advertisers, who stopped running ads in the Press. Although the newspaper reached a subscriber base of 20,000 and received supplemental support from the NAACP, it struggled to remain operational. The intimidation of Black news carriers during the desegregation protests, combined with the advertisers' boycott, forced the Press to close in 1959.

Daisy Bates revived the Arkansas State Press (1984-1998) [LCCN: sn90050043] in 1984—it ran through 1998—and dedicated the paper to the memory of her late husband, Lucius.

For more information about this title, visit https://www.loc.gov/item/sn84025840/.

By the early 1900s, Black Arkansans in Little Rock had created a "city within a city" along West 9th Street comprised of Black businesses, churches, and social halls. Due to Jim Crow laws, Black Arkansans had to run their own businesses, newspapers, and schools. The Mosaic Templars of America (MTA) was one such business founded on 9th Street. This Black fraternal organization offered services like insurance, loans, publishing, schools, and a hospital. By the 1920s, the MTA was one of the largest Black businesses in the United States. As with the rest of the South, Little Rock went through major contested changes during the civil rights movement and in the 1950s; became the center of national attention during the Desegregation of Central High School.

Across the South, segregation meant Black communities had to produce their own newspapers as well, since white papers rarely covered news written for a Black audience. William Alexander Scott, a Black newspaper entrepreneur in Atlanta, Georgia found success publishing advertisement flyers in the city and in 1928, he established the Atlanta World (192?-1932), (later the Atlanta Daily World (1932-current)). Unlike the other national Black newspaper at that time, the Chicago Defender (1906-1966), which had a more militant stance, the Atlanta Daily World was more moderate in its outlook, advocating for basic rights for Black Americans, but stopping short of calling for racial equality.

After the Atlanta World was successfully established, Scott devised the idea of a chain of Black newspapers covering the American South from his base in Atlanta. Knowing the cost of running a newspaper was prohibitive, his plan encouraged the creation of newspapers in small towns by printing the chain newspapers in Atlanta and distributing them to each syndicate member. Members would write local news for their paper and supplement it with stories from the World. In 1931, his plan came to fruition with the creation of the Southern News Syndicate (later also referred to as the Scott Newspaper Syndicate). In 1934, in the midst of growing his successful Syndicate, Scott was murdered on his doorstep in Atlanta. After a brief void in the Syndicate's leadership, members of Scott's family took over to keep the Newspaper Syndicate running. Thanks to the Syndicate, several Black newspapers were able to operate out of Little Rock, including the Arkansas Survey-Journal and the Arkansas World.

While some newspapers were explicitly created as part of the Syndicate, many had already been in publication for years before joining. The Arkansas Survey is an example of one such newspaper. Percy Lipton Dorman, a Black educator, was appointed by Governor Charles Hillman Brough to oversee Arkansas's Black schools in 1917. In 1923, Dorman established the Arkansas Survey in part to advocate for Arkansas's Black schools. The one issue that survives from the Survey on September 20, 1924, called for better facilities for Black students. Dorman was a moderate when it came to the civil rights struggle. Acting as Supervisor of Negro Schools in Arkansas, he was expected to keep the racial status quo, which fit with the Syndicate's overall racial outlook at the time. During his time at the Survey, Dorman also worked at the Mosaic Templars of America. After leaving the Survey, he served as editor for the Arkansas World.

The Survey's financial struggles prompted it to later join the Syndicate in 1935, when it was renamed to the Arkansas Survey-Journal. The Survey-Journal retained its base in Little Rock but had offices in Pine Bluff and Helena as well, towns with large Black communities. By 1940, the paper's business and circulation managers were George W. Scott and Thomas Watson respectively. The rest of the staff were women, several of whom served as the editors. These include Mrs. E. W. Dawson, Alice Young, Sallie Buchanan, Mrs. Ludy Clinkscales, Mrs. F. E. Doles, and Louise Thornton.

Also in 1940, Augustus G. Shields, Jr. created the Arkansas World with Dorman as contributing editor. Shields was an entrepreneur and cofounder of the National Negro Publishers Association. In the one existing issue of the Arkansas World, Shields wrote that the paper was "non-sectarian and non-partisan … supporting those things it believes to the interest of its readers and opposing those things against the interest of its readers."

Though Syndicate members maintained a moderate political and social stance, as the 1940s progressed and Black Americans became more vocal about voting rights, the Atlanta Daily World began to call for equality. Other Syndicate papers soon followed this new editorial policy. The Syndicate remained strong until the mid-1950s when many of the smaller papers began to close. In Arkansas, the Arkansas World closed in 1957 and the Survey-Journal also closed sometime in the 1950s.

As of this writing, there are only a few surviving issues of the Survey and World. This is the case for many Black newspapers, as past archival organizations were often neglectful of preserving the Black community’s written heritage, and the newspapers did not survive. When newspapers disappear, Black voices are forever lost, leaving a large gap in the understanding of our history.

For more information about this title, visit https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn92050012/.

By the early 1900s, Black Arkansans in Little Rock had created a "city within a city" along West 9th Street comprised of Black businesses, churches, and social halls. Due to Jim Crow laws, Black Arkansans had to run their own businesses, newspapers, and schools. The Mosaic Templars of America (MTA) was one such business founded on 9th Street. This Black fraternal organization offered services like insurance, loans, publishing, schools, and a hospital. By the 1920s, the MTA was one of the largest Black businesses in the United States. As with the rest of the South, Little Rock went through major contested changes during the civil rights movement and in the 1950s; became the center of national attention during the Desegregation of Central High School.

Across the South, segregation meant Black communities had to produce their own newspapers as well, since white papers rarely covered news written for a Black audience. William Alexander Scott, a Black newspaper entrepreneur in Atlanta, Georgia found success publishing advertisement flyers in the city and in 1928, he established the Atlanta World (192?-1932), (later the Atlanta Daily World (1932-current)). Unlike the other national Black newspaper at that time, the Chicago Defender (1906-1966), which had a more militant stance, the Atlanta Daily World was more moderate in its outlook, advocating for basic rights for Black Americans, but stopping short of calling for racial equality.

After the Atlanta World was successfully established, Scott devised the idea of a chain of Black newspapers covering the American South from his base in Atlanta. Knowing the cost of running a newspaper was prohibitive, his plan encouraged the creation of newspapers in small towns by printing the chain newspapers in Atlanta and distributing them to each syndicate member. Members would write local news for their paper and supplement it with stories from the World. In 1931, his plan came to fruition with the creation of the Southern News Syndicate (later also referred to as the Scott Newspaper Syndicate). In 1934, in the midst of growing his successful Syndicate, Scott was murdered on his doorstep in Atlanta. After a brief void in the Syndicate's leadership, members of Scott's family took over to keep the Newspaper Syndicate running. Thanks to the Syndicate, several Black newspapers were able to operate out of Little Rock, including the Arkansas Survey-Journal and the Arkansas World.

While some newspapers were explicitly created as part of the Syndicate, many had already been in publication for years before joining. The Arkansas Survey is an example of one such newspaper. Percy Lipton Dorman, a Black educator, was appointed by Governor Charles Hillman Brough to oversee Arkansas's Black schools in 1917. In 1923, Dorman established the Arkansas Survey in part to advocate for Arkansas's Black schools. The one issue that survives from the Survey on September 20, 1924, called for better facilities for Black students. Dorman was a moderate when it came to the civil rights struggle. Acting as Supervisor of Negro Schools in Arkansas, he was expected to keep the racial status quo, which fit with the Syndicate's overall racial outlook at the time. During his time at the Survey, Dorman also worked at the Mosaic Templars of America. After leaving the Survey, he served as editor for the Arkansas World.

The Survey's financial struggles prompted it to later join the Syndicate in 1935, when it was renamed to the Arkansas Survey-Journal. The Survey-Journal retained its base in Little Rock but had offices in Pine Bluff and Helena as well, towns with large Black communities. By 1940, the paper's business and circulation managers were George W. Scott and Thomas Watson respectively. The rest of the staff were women, several of whom served as the editors. These include Mrs. E. W. Dawson, Alice Young, Sallie Buchanan, Mrs. Ludy Clinkscales, Mrs. F. E. Doles, and Louise Thornton.

Also in 1940, Augustus G. Shields, Jr. created the Arkansas World with Dorman as contributing editor. Shields was an entrepreneur and cofounder of the National Negro Publishers Association. In the one existing issue of the Arkansas World, Shields wrote that the paper was "non-sectarian and non-partisan … supporting those things it believes to the interest of its readers and opposing those things against the interest of its readers."

Though Syndicate members maintained a moderate political and social stance, as the 1940s progressed and Black Americans became more vocal about voting rights, the Atlanta Daily World began to call for equality. Other Syndicate papers soon followed this new editorial policy. The Syndicate remained strong until the mid-1950s when many of the smaller papers began to close. In Arkansas, the Arkansas World closed in 1957 and the Survey-Journal also closed sometime in the 1950s.

As of this writing, there are only a few surviving issues of the Survey and World. This is the case for many Black newspapers, as past archival organizations were often neglectful of preserving the Black community’s written heritage, and the newspapers did not survive. When newspapers disappear, Black voices are forever lost, leaving a large gap in the understanding of our history.

For more information about this title, visit https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn92050011/.

Located in central Arkansas, Little Rock is the state capital as well as the county seat of Pulaski County. Early European settlers arrived in the Little Rock area by the 1820s. The city grew quickly and by the late 1800s, Little Rock had a telephone

exchange, electricity, paved cobblestone streets, and sewer lines. The population in Pulaski County surged in the late 1800s and early 1900s, especially in Little Rock.

In 1882, Opie Percival Read and his brother-in-law Philo Dayton Benham started The Arkansaw Traveler in Little Rock. They published the paper every Saturday, with Read working as editor and Benham managing the business. Read chose to name the paper after the Arkansas Traveler folktale, with the paper masthead including an image of a traveler, sheet music, a squatter, and his hut. According to the folktale, which dates as far back as at least 1840, a lost traveler in rural Arkansas asks a squatter for directions. The squatter is unhelpful until the Traveler plays the second half of the tune the squatter had begun on his fiddle. Learning the second part of the song makes the squatter so happy that he offers his hospitality and finally gives the Traveler directions. Read published this story in the first issue of the Traveler.

Read, who had a droll sense of humor, created the Traveler as a humorous literary paper. The Traveler was so popular that it gained national fame for its humor, especially the character sketches, standing out from other general news and political papers. While paper sales increased, some people took offense at Read's humor, which focused on life in the South. Eventually the newspaper lost its popularity as the quality of the writing declined. Read moved to Chicago, and in 1887, The Arkansaw Traveler began publishing out of Chicago as well as Little Rock.

Read wrote several novels and in 1888, he started publishing chapters of his novels in weekly installments in the Traveler. Read's novels included Mrs. Annie Green, Len Gansett, and A Kentucky Colonel. All three of his novels were popular and in early 1892, Read left the Traveler to work on his other literary pursuits. In 1902, The Monticellonian (1870-1920) reported that Read was in New York working as a playwright.

In 1896, the Traveler changed to a monthly publication. The last editor recorded for The Arkansaw Traveler was Harry Stephen Keeler. Keeler was a Chicago native who wrote numerous mystery and science fiction novels. While he published The Arkansaw Traveler, it was listed as a fiction newspaper. By the late 1910s, the Traveler had ceased publication in either city.

For more information about this title, visit https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn90050009/.

The "True Democrat" (1852-57) was first printed on September 7, 1852, in Little Rock, Arkansas by owners and publishers Richard Henry Johnson and Reuben S. Yerkes, with Johnson serving as editor. Its preceding title, the Arkansas Democratic Banner (1851-52), was changed to the "True Democrat" for political reasons. The new publishers described the reason for the name change as "renewed assurances of fidelity to the noble principles of our party... we unfurl to our patrons and the public--'THE TRUE DEMOCRAT.'" The "True Democrat" and its successors--"Arkansas True Democrat" (1857-62) and "True Democrat" (1862-63)--were published as weeklies. Daily editions were published for a short time, including the "Daily True Democrat" (1861) and the "True Democrat Bulletin" (1862-?), but these editions ended due to financial constraints and lack of support.

For more information about this title, visit https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014282/.

Little Rock is the Pulaski County seat and capital city of Arkansas, founded on the Arkansas River banks in the center of the state. After the Civil War, many Black residents settled on West Ninth Street (originally West Hazel Street), where the Union Army had built houses for the newly freed. Black businesses also centered on Ninth Street, in part because of Jim Crow laws enforcing segregation. Newspapers were one of the business avenues opened to Black citizens after the Civil War, and numerous Black-owned papers were founded in the capital city in the late 1800s.

After the Arkansas Freeman (1869-18??) closed in the 1860s, there were no Black-owned newspapers in Little Rock. It was not until August 7, 1880 that another Black-owned paper would appear. Coney O. Jacko (later styling himself as W. C. O. Jacques) was an artist who taught music in Little Rock. In 1880, he turned to the literary arts and founded the Arkansas Weekly Mansion, a 4-page Republican paper published every Saturday. The name of the paper was chosen by Mollie E. Harris, though it is not known why she chose Mansion for the title. The Mansion was sometimes incorrectly cited as the first Black publication in Arkansas, but the Freeman preceded the Mansion by a decade.

Jacko was a supporter of the Greenback Party, which supported greenback money that was not backed by gold. This money, greenback supporters argued, was better for farmers because it helped prevent inflation when money supply increased. Jacko used the Mansion to support Greenback candidates, giving the paper a populist slant. This was unique among other Black publications in Arkansas during the late 1800s, as most focused on arguing for greater civil rights for Black Americans.

After publishing a few issues, Jacko partnered with Henry K. Pittmore, a local businessman, for funding to help run the paper. Later, he and Pittmore decided to split the paper in two, with Jacko running the Mansion, and Pittmore running another Black newspaper whose name is lost to history. The Mansion continued to struggle, and Jacko brought in more investors, including H. H. Jackson, to shore up the mounting debts. However, by the end of 1881, Jacko sold the newspaper to investor D. I. Berry, who took over publishing duties.

The Mansion remained financially insolvent, leading Berry to bring in J. A. Jarrett and Henry Simkens as investors and staff. Simkens, a Canadian citizen who had recently moved to Arkansas, took over as editor and business manager. Simkens stood out among other Black editors in the United States because he took a less progressive stance and used the Mansion to oppose civil rights legislation.

Continuing financial struggles led stockholders to suggest Berry sell to I. B. Atkinson. Atkinson kept the paper running with Simkens as editor for a few months, but eventually stopped paying the staff and suspended the Mansion. Atkinson substituted his new paper, the Reformer. Meanwhile, Jacko bought printing materials from Jarrett and started a rival newspaper titled the Independent, which only lasted a few issues before it closed. Jacko sold the materials back to Berry and moved to Camden. Simkens and Berry organized the Mansion Publishing Company, commencing business on January 1, 1882, with Berry as president and Simkens the editor and business manager.

Despite its financial struggles, within the first few years the Mansion claimed a readership of 1,500 subscribers. It peaked at 2,000 readers in 1883 and 1884, with ads for the Mansion claiming to have the largest circulation of any weekly Black newspaper in the South. In 1883, the Mansion printed accounts of the Howard County Race Riot from several people who lived in the area. The paper went on to provide updates about the Black men who were arrested and charged with murder after the riot.

In the early part of 1884, Simkens wrote disparaging articles about the editors of another Black publication in Little Rock, the Arkansas Herald (established in 1881, publishing on Fridays). In the February 9, 1884 issue, Simkens addressed the Herald Company editors as "those maniacs, whoever they are, that control the columns of the Herald" and claimed that they were "trying to run a newspaper at the expense of their competitors."

By late 1884 the Mansion had combined with the Herald. The two publishing companies combined into the Herald-Mansion Publishing Company to print the combined paper of the Herald-Mansion, with Julian Talbot Bailey from the Herald elected as editor. The Herald-Mansion continued the Mansion's publishing schedule, releasing on Saturdays. Bailey worked at the Herald-Mansion for just a few months before taking a professorship at the Philander Smith University in Little Rock. Despite his short tenure at the Herald-Mansion, Goodspeed's History of Pulaski County said that when Bailey was elected as the Herald-Mansion's editor, the paper "was at once regarded as one of the leading negro journals of the country." In 1885 Bailey joined Edward Allen Fulton's newspaper, the Sun in Little Rock. Fulton had also previously been an editor at the Herald.

After Bailey left the Herald-Mansion, William M. Buford came on as editor. Buford previously worked as a teacher. By November 1885, the Mansion split from the Herald and resumed publication again under the Mansion Publishing Company. Berry returned as president, and in his reintroduction of the paper in the November 21, 1885 issue, claimed the Mansion to be "on a firmer basis than ever before." The Mansion acquired a new office but returned to its roots and brought back the founder of the paper, Jacko, as the editor. In the same issue, Jacko pledged to provide a "newsy paper" that advanced the "cause of education and industry to our race." B. F. Rowan was employed as the printer, with Benjamin Jarrett as general agent to canvass the state, and Mrs. B. F. Fry (whose husband, H. B. Fry, had been an editor at the Herald) as news agent in Texas.

In an 1885 issue, the Mansion rented out space for a page of the Mosaic Guide newspaper, a semi-monthly paper published by Pittmore. The Guide was the official organ of the Mosaic Templars of America (MTA), a Black fraternal organization founded in Little Rock (this Mosaic Guide was a separate publication from the later Mosaic Guide (18??-19??) newspaper for the MTA that began as the American Guide (1889-1???).

In 1886, Jacko served as president of the Colored Press Association. In 1887 the Mansion halted publication for the last time. The Mansion's printing plant was sold to Buford, which he used to start the Arkansas Dispatch. Jacko, under the name Jacques, went on to become a traveling artist and lecturer.

As of this writing, there are few surviving issues of the Mansion and other Black newspapers published in Little Rock around that time. Past archival organizations were often neglectful of preserving the Black community's written heritage, and the newspapers did not survive. When newspapers disappear, Black voices are forever lost, leaving a large gap in the understanding of our history.

For more information about this title visit, https://www.loc.gov/item/sn84020670/.

By the early 1900s, Black Arkansans in Little Rock had created a "city within a city" along West 9th Street comprised of Black businesses, churches, and social halls. Due to Jim Crow laws, Black Arkansans had to run their own businesses, newspapers, and schools. The Mosaic Templars of America (MTA) was one such business founded on 9th Street. This Black fraternal organization offered services like insurance, loans, publishing, schools, and a hospital. By the 1920s, the MTA was one of the largest Black businesses in the United States. As with the rest of the South, Little Rock went through major contested changes during the civil rights movement and in the 1950s; became the center of national attention during the Desegregation of Central High School.

Across the South, segregation meant Black communities had to produce their own newspapers as well, since white papers rarely covered news written for a Black audience. William Alexander Scott, a Black newspaper entrepreneur in Atlanta, Georgia found success publishing advertisement flyers in the city and in 1928, he established the Atlanta World (192?-1932), (later the Atlanta Daily World (1932-current)). Unlike the other national Black newspaper at that time, the Chicago Defender (1906-1966), which had a more militant stance, the Atlanta Daily World was more moderate in its outlook, advocating for basic rights for Black Americans, but stopping short of calling for racial equality.

After the Atlanta World was successfully established, Scott devised the idea of a chain of Black newspapers covering the American South from his base in Atlanta. Knowing the cost of running a newspaper was prohibitive, his plan encouraged the creation of newspapers in small towns by printing the chain newspapers in Atlanta and distributing them to each syndicate member. Members would write local news for their paper and supplement it with stories from the World. In 1931, his plan came to fruition with the creation of the Southern News Syndicate (later also referred to as the Scott Newspaper Syndicate). In 1934, in the midst of growing his successful Syndicate, Scott was murdered on his doorstep in Atlanta. After a brief void in the Syndicate's leadership, members of Scott's family took over to keep the Newspaper Syndicate running. Thanks to the Syndicate, several Black newspapers were able to operate out of Little Rock, including the Arkansas Survey-Journal and the Arkansas World.

While some newspapers were explicitly created as part of the Syndicate, many had already been in publication for years before joining. The Arkansas Survey is an example of one such newspaper. Percy Lipton Dorman, a Black educator, was appointed by Governor Charles Hillman Brough to oversee Arkansas's Black schools in 1917. In 1923, Dorman established the Arkansas Survey in part to advocate for Arkansas's Black schools. The one issue that survives from the Survey on September 20, 1924, called for better facilities for Black students. Dorman was a moderate when it came to the civil rights struggle. Acting as Supervisor of Negro Schools in Arkansas, he was expected to keep the racial status quo, which fit with the Syndicate's overall racial outlook at the time. During his time at the Survey, Dorman also worked at the Mosaic Templars of America. After leaving the Survey, he served as editor for the Arkansas World.

The Survey's financial struggles prompted it to later join the Syndicate in 1935, when it was renamed to the Arkansas Survey-Journal. The Survey-Journal retained its base in Little Rock but had offices in Pine Bluff and Helena as well, towns with large Black communities. By 1940, the paper's business and circulation managers were George W. Scott and Thomas Watson respectively. The rest of the staff were women, several of whom served as the editors. These include Mrs. E. W. Dawson, Alice Young, Sallie Buchanan, Mrs. Ludy Clinkscales, Mrs. F. E. Doles, and Louise Thornton.

Also in 1940, Augustus G. Shields, Jr. created the Arkansas World with Dorman as contributing editor. Shields was an entrepreneur and cofounder of the National Negro Publishers Association. In the one existing issue of the Arkansas World, Shields wrote that the paper was "non-sectarian and non-partisan … supporting those things it believes to the interest of its readers and opposing those things against the interest of its readers."

Though Syndicate members maintained a moderate political and social stance, as the 1940s progressed and Black Americans became more vocal about voting rights, the Atlanta Daily World began to call for equality. Other Syndicate papers soon followed this new editorial policy. The Syndicate remained strong until the mid-1950s when many of the smaller papers began to close. In Arkansas, the Arkansas World closed in 1957 and the Survey-Journal also closed sometime in the 1950s.

As of this writing, there are only a few surviving issues of the Survey and World. This is the case for many Black newspapers, as past archival organizations were often neglectful of preserving the Black community’s written heritage, and the newspapers did not survive. When newspapers disappear, Black voices are forever lost, leaving a large gap in the understanding of our history.

For more information about this title, visit https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn92050010/.

Batesville is the Independence County seat in northeastern Arkansas. Located on the White River, the town developed from a major mercantile port to the cultural center of the region by the mid-1800s. However, the Civil War devastated the town with several military actions occurring there and occupation changing between sides multiple times. Elisha Baxter, previously Batesville's mayor, became Arkansas's last Republican governor during Reconstruction. In the late 1800s, railroad lines were built through town, largely replacing the river traffic. Batesville had a vibrant newspaper industry, producing many newspapers for every variety of political affiliation, from Know-Nothings to Republicans. Enterprising Batesville newspeople regularly created, combined, and transferred between newspapers in town during their careers.

In 1877, at the end of Reconstruction, Franklin Desha Denton started the Batesville Guard. Denton was a Batesville native who served in the Confederate Army. Postwar, he was elected county sheriff, and after several unsuccessful mercantile ventures, he founded the Guard. This four-page, Democratic paper was published once a week and had a circulation of over 500 people. In 1880, Denton brought on Walter Robert Joblin as associate editor, but Joblin died the next year at 35 years old.

A fire on February 20, 1880, destroyed the Guard's office, along with several other buildings on Main Street in Batesville. The fire was suspected to be arson, with reports that an incendiary under the floor of E. W. Clapp & Co.'s store started the fire. A rival newspaper in town, the North Arkansas Pilot (1879-1888), helped the Guard recover. Denton bought new supplies from New Orleans, Louisiana, and the paper resumed weekly publication on April 1, 1880, missing just five issues.

Denton sold the Guard in 1885 to go work as the Batesville Postmaster. In the 1890s, Denton established the Batesville Weekly Bee (1892-189?), but by 1900 he quit the papers and moved to Memphis, Tennessee.

Milton Y. Todisman took over the Guard in 1885 and ran it for a few years. John L. Tullis bought the paper next and worked as editor until 1890, when Edgar L. Givens purchased the paper. Givens had previously published the Washington Press (1883-1???) in Washington, Arkansas. He then temporarily moved to Washington, D.C. to work as secretary for Arkansas Senator James Kimbrough Jones. In 1893, after working for a few years at the Guard, Givens moved to Little Rock to help publish the Arkansas Gazette (1889-1991) after the editor, Daniel Armod Brower, left due to ill health. Givens returned to Batesville a few years later to resume working at the Guard. In 1905, he added a daily edition of the Guard in addition to the weekly edition. In later years, the Guard printed a twice-a-week version as well.

Under Givens, a stock publishing company for the Guard was formed, the Batesville Printing Company. In 1907, the company brought on George Harris Trevathan to act as the Guard's manager and editor. Trevathan's newspaper career began in his teens when he worked at the North Arkansas Pilot under William Wilson Byers. In 1890, Trevathan married Nellie Hunt of Melbourne. In 1892, Trevathan started the Democrat in Melbourne, which he ran for a few years before moving back to Batesville. In Batesville, he took over the Progress (1889-18??) from Todisman, who had moved to the Progress after working at the Guard previously. Trevathan later moved to Mammoth Springs and combined two papers into the Banner=Nugget (1???-190?), later renaming it the Salem Banner (190?-1924). Trevathan worked as journal clerk for the House of Representatives, secretary of the State Senate, and bookkeeper in the State Treasurer's office. In 1905, he returned to the newspaper business in Batesville, purchasing the Weekly Bee (189?-1905) and renaming it the Independence County News (1905-1907). In 1907, when Trevathan joined the Guard, he consolidated the Independence County News into the Guard. In the 1910s, Trevathan's health took him away from the Guard at various points, leaving the state several times with his family in attempts to recover his health. During these periods, other editors were brought on for short stints at the Guard.

At first Trevathan claimed retirement due to his health, selling his interest in the paper in 1910 to Gainer Owen Duffey, who became editor and business manager. In 1911, however, Trevathan returned to Batesville and bought out Duffey. Dene Hamilton Coleman, former Batesville mayor and state representative, came on as editor from 1911 to 1912.

In 1913, Robert Presley Robbins joined Trevathan and together they bought out Givens's stock. Givens died a few months later. Robbins was active in newspaper publishing, founding and working at newspapers around Arkansas and Tennessee. After editing the Guard for a year, Robbins left in 1914 to run the Arkansawyer (190?-1915) in Stuttgart.

From 1913 to 1914, Trevathan used the Guard to speak against Congressperson William Allan Oldfield's reelection campaign. Oldfield had practiced law in Batesville before his first election to Congress in 1908. Trevathan said he was Oldfield's best friend but had some complaints about how he handled the appointment for the postmaster position. Oldfield published his rebuttal in other newspapers across the state, claiming the Guard was printing falsehoods and slander because Trevathan was upset he was not given the Batesville postmaster position. Despite the back and forth, voters reelected Oldfield to Congress. He remained in Congress until his death in 1928. His wife, Fannie Pearl Peden Oldfield, was elected to take his place, becoming the first Arkansas Congresswoman.

In 1914, Claude Lee Coger bought Trevathan's interest in the Guard. Coger had previously owned and edited the Sharp County Record (1877-1976) for 20 years. Coger hired his nephew, Austin Coger Wilkerson, as associate editor of the Guard. Wilkerson had also worked with his uncle at the Record. Coger ran the Guard for a few months before returning to the Record, and Wilkerson took charge as editor. Wilkerson stayed on until 1916, when he left to work at other newspapers, and Trevathan resumed his duties at the Guard.

In 1917, Trevathan's ill health again sent him away. This time he remained in state, going to the Booneville Sanatorium to treat his tuberculosis. However, he died from the disease several months later. His wife, Nellie Trevathan, and son Joseph "Allen" Trevathan stepped up to run the Guard, with Allen working as business manager and Nellie as editor. Allen died the following year at 26 years old from influenza that developed into pneumonia. He left behind two children and a pregnant wife. The Trevathan's other son, Jared Edwin Trevathan, was serving in World War I. He was given an honorable discharge from the American Expeditionary Forces to return home to help his mother. Jared filled his brother's position as the Guard's business manager. By this point, the paper had a circulation of over 2,000, and Jared and Nellie ran the paper together until 1931. While at the Guard, Nellie also wrote articles for papers around the state, including the Arkansas Gazette (1889-1991). She served as poet laureate of the Arkansas Press Association and was active in many civic organizations and charity work. She died in 1942 in Little Rock.

In 1932 Oscar Eve Jones and wife Josephine Phillips Carroll Jones bought out the Trevathans and took over the Guard. The Jones' also owned the Batesville Record (1915-1982). During his time at the Guard, Oscar served as president of the Arkansas Press Association and state senator.

The Guard continues to publish in Batesville today. It is the only newspaper that has maintained its run in Batesville since the 1880s, despite the many other papers printing there over the years.

For more information about this title, visit https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn90050268/.