Permanent Exhibits

Portions of our permanent collection may be temporarily closed during our renovation project. The Arkansas Black Hall of Fame is open on the third floor.

Mosaic Templars Cultural Center (MTCC) is a museum of the Department of Arkansas Heritage dedicated to Arkansas' African American history and culture, including keeping alive the legacy of the Mosaic Templars of America and the historic West Ninth Street District. The museum holds permanent exhibits for year-round viewing.

Children's Gallery "Same. Different. Amazing."

This children's gallery is designed for ALL children, ages 0 to 9, to learn how we can grow by celebrating our diversity and discovering what makes each of us amazing. Explore "Same. Different. Amazing." in this one-of-a-kind children’s gallery.

New 360-degree Theater

This gallery showcases a custom-made video.

A Building for the Community

The History of the Mosaic Templars of America Building

The National Grand Temple of the Mosaic Templars of America served as an important commercial and community center for African Americans in Little Rock between 1913 and 1939. It was built under the leadership of Mosaic Templars Grand Master William Alexander on land purchased at the corner of West Ninth Street and Broadway in 1912.

More than 2,000 people gathered to hear Booker T. Washington dedicate the new building October 15, 1913. The new, multipurpose three-story structure had retail space on the bottom floor for businesses such as Dr. W.O. Foster's pharmacy, second-floor office space for professionals, and a third-floor auditorium for community events. The Mosaic Templars subsequently built two more structures along Broadway: the Annex in 1918 (burned in 1984), and the State Temple in 1921.

The Mosaic Templars, after going into receivership in 1930, ceased to have a presence in the National Grand Temple. In the 1930s the building was occupied by a few black professionals, including Dr. John M. Robinson and attorney John H. Hibbler. From the 1940s into the 1990s, the National Grand Temple was occupied by an automotive supply company, a moving and transport company, and an upholstery shop. At times, it sat vacant.

By the late 20th century, the National Grand Temple was in disrepair and threatened by demolition from developers. The Society for the Preservation of the Mosaic Templars of America Building was formed in 1992 to save the building. Their efforts, along with the support of the Arkansas Legislative Black Caucus, led to the creation of the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center in 2001. While under renovation, the National Grand Temple was destroyed by fire in March 2005.The Department of Arkansas Heritage began to build a new structure for the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center in 2006 on the original site.

Little Rock's West Ninth Street Business District

Little Rock's West Ninth Street emerged as the economic and social center of Little Rock's African American community in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In a segregated economy, the black-owned businesses in the district were a source of pride, security and independence for the community.

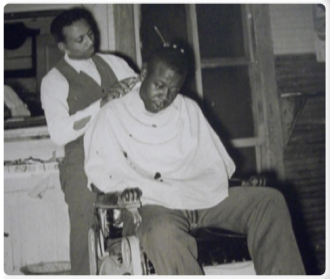

The West Ninth Street business district served the needs of the community when Jim Crow kept services elsewhere unequal. Barbershops, restaurants, hotels, undertakers and jewelers lined West Ninth Street. African American physicians and pharmacists such as Drs. William J.E. Bruce, William O. Foster and Frank B. Coffin served their community with offices on West Ninth Street.

The West Ninth Street business district was also a social and entertainment center. Churches such as First Missionary Baptist and Bethel African Methodist Episcopal had deep roots here. Auditoriums in the Mosaic Templars National Grand Temple and the Dreamland Ballroom in Taborian Hall held graduations, basketball games, dances and musical performances.

Business declined in the 1930s due to the Great Depression, but World War II brought renewed growth and activity in the 1940s and 1950s. Business again declined in the 1960s as urban renewal and the construction of housing projects and highways changed the city's landscape.

A City Within a City

The experience of African Americans in Arkansas is as varied as the landscape of the state. From the fields of the Delta to the industries of southern and western Arkansas to the hustle and bustle of urban centers, the story of black Arkansans is rich in history and deeply rooted in heritage.

The Emancipation Proclamation and the arrival of federal troops in 1863 meant the abolition of slavery in Arkansas. The promised freedom was curtailed by racial discrimination and a political system that failed to protect the political, social and economic rights of black Arkansans.

Active in civil rights, education, church organizations, recreational activities and politics, black Arkansans have made an indelible mark on the state. Arkansans such as James T. White of Phillips County, who was elected to the Arkansas General Assembly in 1871, W. Harold Flowers, a lawyer from Pine Bluff who championed the right to vote, and Edith Irby, the first African American to graduate from the University of Arkansas Medical School, have led by example and inspired generations of black Arkansans. These stories and countless others make up the fabric of Arkansas's African American history.

African Americans in Arkansas, 1870 to 1970

Entrepreneurs recognize an opportunity to start a new business and use whatever resources are available to them to make the opportunity a steppingstone for success. Historically, African-American entrepreneurs have incorporated ideals of self-help, economic independence and an economic cooperative spirit. Before the Civil War, the opportunity for ownership was a rarity for black Arkansans; however, after 1865, black business ownership began to greatly increase. The end of the Civil War brought freedom and success for some blacks, but it also brought laws that legalized segregation and denied equal opportunities.

The rise of a Jim Crow South, along with a hunger for ownership and economic freedom, created the right environment for blacks to have an opportunity to establish their economic independence. Black business districts began to develop in Little Rock, Pine Bluff, Helena, El Dorado and other Arkansas towns to meet the needs of the underserved black population.

Black entrepreneurs began to succeed in many areas. Blacks began to obtain farmland and establish themselves as successful farmers and businessmen. Blacks also used the trades and occupations they learned as slaves, such as blacksmithing, shoemaking, carpentry, laundering and barbering, as a way to create their own economic success, thus becoming Arkansas's first black

Entrepreneurial Spirit

Brotherhood and the Bottomline: The Mosaic Templars of America

The Mosaic Templars of America

The Mosaic Templars of America was an African American fraternal organization founded in Little Rock in 1882 and incorporated in 1883 by two former slaves, John E. Bush and Chester W. Keatts. The organization was established to provide important services such as burial insurance and life insurance to the African-American community. Like many fraternal organizations, the Mosaic Templars' burial insurance policies covered funeral expenses for members, both men and women, who maintained monthly dues.

By 1913, the burial insurance policy also included a Vermont marble marker. These markers are still found in cemeteries across Arkansas and other states. As membership grew, the Mosaic Templars expanded its operations to include a newspaper, hospital, and building and loan association. The organization attracted thousands of members and built a complex of three buildings at the corner of West Ninth Street and Broadway. In July 1930, the Mosaic Templars of America went into receivership. The organization struggled to regain its status, but by the end of the decade it had ceased operations in Arkansas.

A Living History: The Arkansas Black Hall of Fame

The Arkansas Black Hall of Fame Foundation is a nonprofit organization that provides grants to other charitable endeavors in the black community to enhance youth development, health and wellness, education and business/economic development.

The Arkansas Black Hall of Fame seeks to correct the omissions of history and to remind the world that black history is a significant part of American history. The foundation seeks to provide an environment in which future generations of African Americans with Arkansas roots will thrive and succeed.

Each year, the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame acknowledges and celebrates the accomplishments of African-American Arkansans by honoring at least six individuals at the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame Annual Induction Ceremony. Established in 1992, the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame has inducted 85 individuals, including poet Maya Angelou, civil rights attorney Wiley Branton Sr., athlete Sidney Moncrief and musician Pharaoh Sanders.

The Mosaic Templars Cultural Center and the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame partnered to create an exhibit where visitors can learn about the success and talents of Hall of Fame inductees. Housed on the third floor of the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center, the exhibit highlights art, music, sports, education and civil rights by emphasizing the achievements of black Arkansans beginning in the early 20th century.