In 1903, the popular traveling Wild West shows featuring Buffalo Bill and Annie Oakley were starting to lose steam. Audiences who had once flocked to the local fairgrounds to see spectacles of horsemanship, fancy shooting and the exploits of legendary cowboys were starting to find other means of entertainment. Meanwhile, the “Old” West was rapidly disappearing or seemed to be, the automobile having overtaken the horse as a means of transportation. But in the early twentieth century, the Old West would find a new life in cinema houses across the country. Audiences would be thrilled by exploits of cowboys and outlaws in the comfort of a crowded room. Over the next 60 years, the western movie would become one of the most popular attractions at the theater, accounting for one fifth of all American movies produced. Ironically, this vastly popular genre had its beginnings with a film shot not in the sweeping vistas of the far west but, instead, in and around Essex Park, New Jersey; its star was not a sunburned and weathered expert horseman of the plains, but a vaudeville player hailing from, of all places, Arkansas.

Before 1900, most films were short documentaries. The director merely placed a camera on a street corner and filmed people as they went about their daily lives. There were no ideas of using film to tell a fictional narrative. This began to change however, when French director Georges Méliès began developing narrative techniques, including film trickery, to depict fictional stories on the screen.1

With narrative filmmaking in its infancy, Edwin Porter, a camera operator in Thomas Edison’s New Jersey film department, studied Méliès’ work with an interest in taking some of his techniques and improving them. Porter decided that what previous films lacked was a sense of dynamism. He experimented with organizing a series of shots to make the action more intense. One of his early experiments in editing a series of shots together came in 1903 with The Life of an American Fireman, in which he cut between shots of a fireman outside a burning building and interior shots of a family trapped inside the burning building. The whole film was six minutes long.2

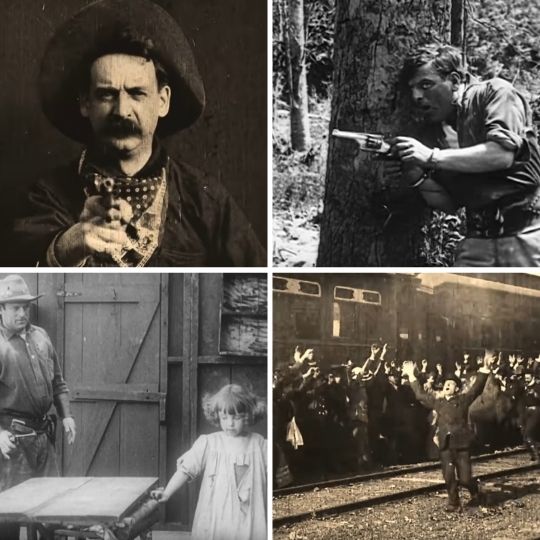

Later that year, Porter began work on another film, The Great Train Robbery. He continued to develop the technique of cutting between scenes as he had in The Life of an American Fireman. In all, he used 14 shots to tell the story of a train robbery gone bad. The plot was simple: villains attack a train depot, then a train passing through the depot. A classic gunfight erupts as the outlaws attempt to rob the train and then flee into the countryside. In the end, law enforcement is able to round up and kill all of the outlaws. The film ends (or begins, depending on which version of the film is being viewed) with the leader of the outlaws pointing his pistol at the audience and then firing.

While making The Great Train Robbery, Porter learned that he could use careful editing tricks to make the audience believe that the production had a large cast, even though he had only a few actors on the set. This ruse was aided by the fact that the camera was static, meaning that he would not be filming any close-ups of actors’ faces. This made the actors unrecognizable as individuals. It was unlikely that the viewing audience would realize that the actor playing the victim of a hold up in a train station was also playing one of the robbers who pulled a gun on the victim. And since Porter had only a few actors to choose from, he chose a young vaudeville player, one Gilbert M. Anderson, to play several of the characters.

Anderson was born Max Aronson, to New York natives, on March 21, 1880, in Little Rock, Arkansas. Max’s father, Henry Aronson, was a traveling salesman. In Little Rock, they lived at 713 Center Street, which today is part of the First United Methodist complex. At the age of three, the family moved to Pine Bluff. He lived in Pine Bluff until 1888 when they moved again to St. Louis where he spent the rest of his childhood. At the age of 18, he moved to New York and changed his name to the less ethnic sounding Gilbert M. Anderson. He soon found work in the blossoming vaudeville circuit in the city. In October 1903, Anderson was on the road with a touring company performing the play His Majesty and the Maid. Lackluster ticket sales led the company to cancel the tour and Anderson found himself back in New Jersey, working for Thomas Edison’s film studio, where he was cast in a short film titled The Messenger Boy’s Mistake.3

Porter, organizing the cast for The Great Train Robbery, asked Anderson to fill three of the roles in the film: one of the robbers, a dead train passenger and a passenger who is shot in the back as he attempts to flee. There was a problem, however: unbeknownst to Porter, Anderson could not ride a horse. When Porter yelled action, Anderson quickly fell from his mount. Pressed for time (the film went into production in the first week of November and was slated for release two weeks later), Porter simply filmed Anderson’s scenes with the actor running on foot.4

At the beginning of production, Porter attempted to make a deal with local railroad companies, promising free publicity in exchange for use of their trains and facilities. As one might expect, the railroad management balked at the idea of using their trains in the film. After all, showing a robbery of the trains could hardly be useful as advertising. Eventually, one relented with the promise that the Edison company would make films suitable for advertising soon. Porter set up his camera to film from a train from the Delaware and Lackawanna Railroad as it sat at a station in Dover, New Jersey. All in all, the film cost $150 ($4,631.18 in 2021 dollars) to make, a bargain even now.5

The film, running as long as twelve minutes in its original form, proved to be wildly successful. Audiences were thrilled to see this epic story being played out in what they believed to be the mountain west. But audiences were being fooled again by cinema trickery. The film was not shot in the west as they believed. Intrepid viewers from New York noticed that they could recognize a few of the actors in the play as natives of New York, with one exclaiming, “Wonder what those fellows were doing out in the Rockies?” Many were surprised to learn that this story of the Wild West was being filmed within fifteen miles of New York City.6

Because of this success, the Western as a genre was forever cemented upon the moviegoers’ psyche. However, the character of the cowboy or outlaw remained a vague idea. The cowboys in The Great Train Robbery were interchangeable with no discernible personalities. This was aided by the fact that Porter filmed only one close up in the film (the closing shot of the outlaw leader shooting a pistol at the audience). The film produced no stars. It was the spectacle that drew audiences, not the actors. This would change after one of those actors, the triple-cast Gilbert M. Anderson, decided to make his own movies.7

After filming The Great Train Robbery, Anderson left Edison’s studio to work at Vitagraph. He began directing shorts and struck gold when his film, Raffles, the Amateur Cracksman, filmed in 1905, became a hit. In 1907, Anderson formed his own film production company with fellow Edison studio alumnus George Spoor. Taking the first letters of each partner’s respective names, Anderson and Spoor named their new company “Essanay.” In 1908, Anderson and Spoor moved their studio to California. The first westerns produced by Essanay were not successful. Anderson later recalled, “Something was lacking. I decided we needed a central character in the films, someone the audience could pull for.” Anderson started looking for stories that featured distinct characters in order to attract audiences.8

That same year, Essanay studios found the solution when they began filming an adaption of a Peter B. Kyne novel, The Three Godfathers. Lacking the actual legal rights to the copyrighted work, Anderson changed a few aspects of the story and renamed some of the characters. Lacking any male stars available to star in the new film, titled Broncho Billy and the Baby, Anderson chose to play the title role. Anderson was able to infuse into the previously lifeless cowboy character a sense of personality. Further, he used the closeup to denote facial expressions in order to convey emotion to the audience. Anderson’s Broncho Billy, was a hard shootin’, hard fightin’, cowboy with a heart of gold. Moreover, Broncho Billy had a personality that audiences could admire.9

The film was an instant success. Anderson decided that he should continue to make films starring Broncho Billy. Even in 1908, film executives knew the value of a good sequel. Meanwhile, Anderson continued to work on his skills as an actor. His acting in the early Bronco Billy films was rather stilted. As the years went on, Anderson’s acting improved as did his horsemanship. He ultimately acted in hundreds of short westerns, most under ten minutes long. Nevertheless, the studio cranked out films at a rate of one a week at its height. In 1911, at the peak of his popularity, a writer remarked of Broncho Billy, “His face is as familiar to the people of this country as that of President Taft’s. He has been photographed millions of times and the photographs are seen by not less than three hundred thousand daily.”10

Essanay under Anderson’s leadership became one of the first movie studios to actively promote its stars. It established a fan newsletter, The Essanay News, which was packed with stories promoting its films and stars. When it came to Broncho Billy, Essanay sent stories to newspapers and magazines across the country about its western star. It created the myth that Anderson came from a long background as a cowpoke, and that his character on screen was synonymous to Anderson’s real life. A news release from 1913 advertising Anderson’s visit to Pine Bluff to see his brother reported, “And Broncho Billy, the desperado, hero of a hundred gun fights, sought by a score of sheriffs, shot no less than 2000 times by count and killed on 11 different occasions, he really is… despite his sensational career Broncho Billy is still hale and hearty and none the worse for wear – except a few bruises and a powder burn or two where some desperate villain fired too close to him.” Another story about his visit to Hot Springs in 1913 warned star-struck female fans that Broncho Billy’s wife would be with him while he was in the Spa City.11

As part of its marketing campaign, Essanay printed stories in the Essanay News urging fans to stop by its studios to meet its stars. Often these stories would promote the idea of visitors being asked to star in impromptu films. This caused a frenzy as fans flocked to the studios. The Essanay News had to print a story that it would no longer allow visitors to star in its films and urged fans to stay away.

In 1916, Anderson seemed to have tired from acting and decided to retire from the screen. He bought a theater in New York City and produced plays, none of which were financially successful. He went into film producing, being responsible for Stan Laurel comedies including the first pairing of Laurel with Oliver Hardy in 1919. After infighting with studio executives, Anderson again retired from the motion picture business, preferring to manage theaters and produce traveling shows instead.13

The theaters he owned failed and, by the mid-1920s, Anderson was struggling financially. Newspaper reports were that he was living off charity from friends and family. He had a slight career revival in the early 1940s, but never recaptured his fame. He again produced films in the early 1950s, but that was short lived, and he retired again, this time for the last time.14

By 1958, Anderson was living quietly in Los Angeles. He was largely forgotten by the industry that he helped build when he received a surprise telephone call. Bob Thomas, a reporter for the Associated Press, wanted to do a story on this forgotten film pioneer. Anderson at first decided against granting the interview, but after Thomas called several times, he relented. He spoke freely to the reporter about his career. After the interview, Thomas wondered why the Motion Picture Academy had not recognized his importance to the development of the western by giving him an honorary Oscar, after all, they had given lifetime achievement Oscars to D.W. Griffith and other luminaries. Thomas called George Seaton, president of the Motion Picture Academy to discuss Anderson’s importance. Seaton agreed and presented the case to the board of governors.15

They unanimously agreed to award Anderson with an Oscar. At the age of 78, Anderson stepped out on stage at the Pantages Theater in Los Angeles to accept his award. He was nervous, especially for a person who had largely been out of the spotlight for so long. Bette Davis gave him his award. Asked after the ceremony if he wanted to revive his career he said, “It’s kinda hard to start a new career at my age. . . . but I might do a few things. They’d have to be worthwhile, though, nothing undignified.”16

He was self-deprecating to the end. Asked to sum up his career and importance Anderson said, “I suppose I did help build the movie business. But if it hadn’t been me, it would have been someone else. Shucks, there was no stopping the motion picture; it had to grow no matter what anyone did to it.” Anderson died in 1971 and was buried in the Chapel of the Pines Cemetery in Los Angeles. In Pine Bluff, he is honored on a downtown mural; the house in which his family lived during the 1890s still stands, on that city’s West 2nd Street.17

View Films Here

The Great Train Robbery (1903)

Broncho Billy’s Christmas Dinner (1911)

Broncho Billy and the Rustler’s Child (1913)

1 John Fell, A History of Films (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1979), 41-43.

2 Charles Musser, Before the Nickelodeon: Edwin S. Porter and the Edison Manufacturing Company (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991), 213-230; William K. Everson, American Silent Film (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978), 36-37.

3 Dave Wallis, “’Broncho Billy’ Anderson.” CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas. https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/broncho-billy-anderson-534/ (Accessed August 31, 2021); Musser, 253-254.

4 Robert Cochran, Suzanne McCray, Lights! Camera! Arkansas! From Broncho Billy to Billy Bob Thornton (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2015), 2-3.

5 The New York Times, March 13, 1904; The Lincoln Star, April 5, 1904; Norman V. Richards, Cowboy Movies (Greenwich, Conn.: Bison Books, 1984), 28.

6 Tacoma News Tribune, March 22, 1904.

7 Everson, 240-243.

8 San Bernardino County Sun, February 22, 1958; Oakland Tribune, February 3, 1974.

9 Everson, 241-242.

10 Ibid., 241; Oakland Tribune, February 3, 1974.; Elmood, Indiana Call-Leader, November 3, 1911.

11 Cochrain, 2-3. Pine Bluff Daily Graphic, January 21, 1913; Hot Springs New Era, January 23, 1913.

12 For an example of such a talent call, see “Who Will Play Dorothy?” advertisement in The Sacramento Star, October 29, 1914.

13 David Kiehn, Broncho Billy and the Essanay Film Company (Berkely: Farwell Books, 2003), 162-165; Los Angeles Highland Park News Herald and Journal, January 24, 1971.

14 Highland Park News Herald and Journal, January 24, 1971.

15 New York Times, March 27, 1961; Jennifer Bean, Anne Morey, et al., Flickers of Desire: Movie Stars of the 1910s (New York: Rutgers University Press, 1911), 28-32; North Hollywood Valley Times, April 4, 1958.

16 Ibid.

17 Salem Capital Journal, April 7 1958; Oakland Tribune, January 21, 1971; Dave Wallis, “’Broncho Billy’ Anderson.” CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas. https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/broncho-billy-anderson-534/