(This is the first in a series about some of the more offbeat and colorful personalities that have graced the political history of Arkansas. A previous article about an earlier figure in this genre, Volney V. Smith, the last lieutenant governor of Arkansas during Reconstruction, is featured on this page under the title, “Just Can’t Get Any Respect.”)

William Hope Harvey filled many career roles in his long life: teacher, lawyer, silver mine owner, finance expert, writer and publisher. He also served as construction developer for a great exposition hall in Colorado and a major resort in Northwest Arkansas. He advocated for free coinage of silver long after William Jennings Bryan and aspired to be President of the United States. Harvey’s life was indeed a complicated journey full of eccentricities. His unique story even extended beyond his grave, as his tomb had to be moved to prevent it from being submerged with the rest of his creations under what is now Beaver Lake.

A West Virginia native, Harvey first taught school there. He later earned a law degree and practiced in Gallipolis, Ohio,and Chicago, Illinois. Then, Harvey and his family moved to Colorado and operated one of the state’s most productive silver mines. After silver prices collapsed, Harvey practiced law, dabbled in real estate and helped develop an ornate exposition hall. Harvey attempted to organize a carnival in Ogden, Utah, but it failed financially.

His contemporaries referred to him as a prophet, a visionary, a genius, a promoter, a flim-flam man, a fraud, a planner and a schemer. In a 2016 Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette article, James F. Hales said Harvey “had an ego that knew no limits and appeared to some as soft spoken, but cold and aloof. … Harvey always aligned himself with the rich and powerful and had an incredible talent for convincing them to invest in his ventures.”

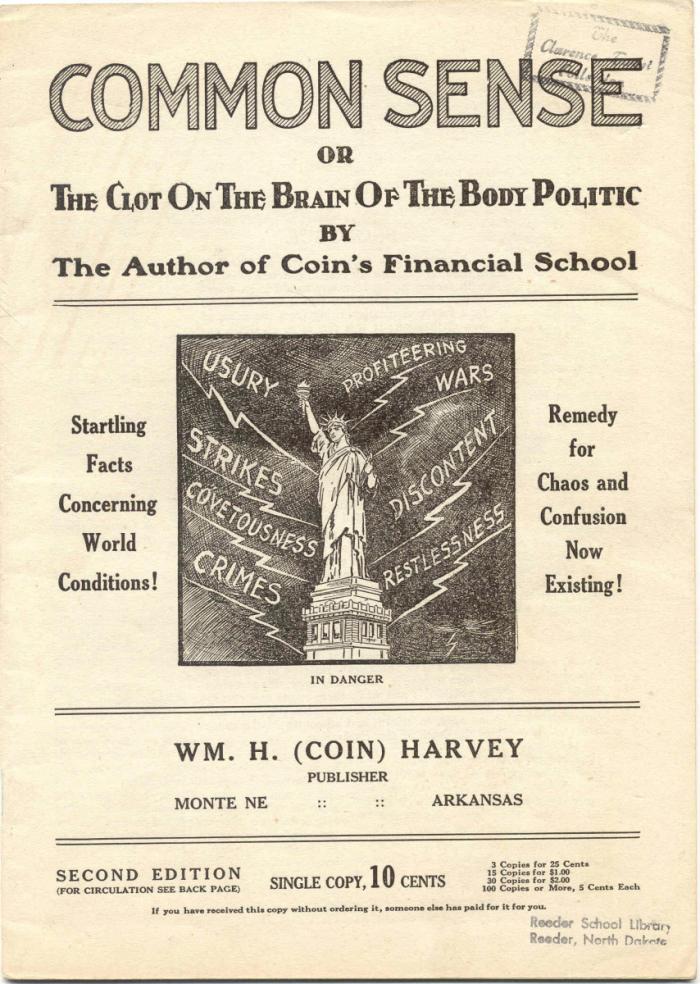

By the early 1890s, as economic depression swept the country, Harvey was swept up in the growing agrarian-based Populist movement that argued for a wide range of political and economic reforms, including abandoning the nation’s long-held policy of backing its currency with gold. In 1894, as the movement was beginning to gather steam, Harvey wrote a beast selling book, “Coin’s Financial School,” in which a fictional young financier named “Coin” presented the case for free silver. Not only did the book bring him fame and fortune, but it also gave him his nickname, “Coin.” Harvey became free silver cause’s most visible spokesman. He campaigned actively for William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic free silver candidate, in 1896 and again in 1900.

By the early 1890s, as economic depression swept the country, Harvey was swept up in the growing agrarian-based Populist movement that argued for a wide range of political and economic reforms, including abandoning the nation’s long-held policy of backing its currency with gold. In 1894, as the movement was beginning to gather steam, Harvey wrote a beast selling book, “Coin’s Financial School,” in which a fictional young financier named “Coin” presented the case for free silver. Not only did the book bring him fame and fortune, but it also gave him his nickname, “Coin.” Harvey became free silver cause’s most visible spokesman. He campaigned actively for William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic free silver candidate, in 1896 and again in 1900.

While campaigning for Bryan, Harvey visited Rogers in Benton County and found there were no large cities or wealthy people. Attracted by the area’s natural beauty, Harvey relocated there when he eased away from politics after 1900. Harvey bought 320 acres of the lush valley originally called Silver Springs and set about to develop it into a fabulous resort. Harvey renamed the site “Monte Ne,” which he claimed to be the Spanish and Native American words for “mountain” and “water.”

Shortly after the Harveys settled in Benton County, their home burned to the ground. Anna Harvey returned to Chicago soon after, and she and her husband were separated until they finally divorced in 1929.

Despite the personal troubles, Harvey forged ahead with developing his resort showplace. By the summer of 1901, the Hotel Monte Ne opened, and as the years progressed, the development expanded to include two more hotels, a tennis court and Arkansas’s first indoor swimming pool. He also built a railroad spur linking Monte Ne to the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad and purchased a gondola from Italy to transport guests from the train station across a spring-fed lagoon to his hotels. In 1913, Harvey founded the Ozark Trails Association (OTA) with a stated purpose of developing better roads. The OTA did little to increase the resort’s business, though, and ultimately Monte Ne was hurt by the growth of automobile travel. In the 1920s, most of the development was sold or foreclosed by the banks.

The failure of Monte Ne slowly altered both Harvey’s world view and his personality. By the mid-1920s, Harvey became convinced that civilization was doomed. So, in 1926, he started his 'great pyramid' project - building a 140-foot high concrete time capsule in the form of an obelisk in order to preserving civilization’s history. He envisioned the time capsule would contain all the inventions and writings of the day. He believed that in the future, mankind would return to Monte Ne, open the pyramid, read about the reasons for the failure of civilization and avoid the same mistakes. He also had a retaining wall built as an amphitheater on the site.

As he advanced in years and his health began to fail, Harvey veered back into politics. He failed in a bid for Congress, and by the time of the Great Depression, most of his investments had been wiped out in the stock market. The Liberty Party, which he formed in 1931, focused on economic reform and adopted the free silver mantra of the Bryan era. Harvey was the only candidate the delegates could agree to at their convention, held at Monte Ne’s amphitheater. Harvey managed just more than 54,000 votes, of which barely over 1,000 were from Arkansas. Only two of those came from Benton County.

Harvey’s health and finances continued to decline, and he died at his beloved Monte Ne on Feb.11, 1936. The man affectionately called “Coin” was buried beside one of his sons in a concrete tomb near his amphitheater. The tomb was later moved and now overlooks present-day Beaver Lake.