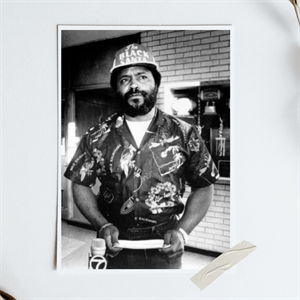

“Say” Mcintosh was a true multifaceted figure: alternately compassionate, concerned, outraged, outrageous, bombastic, dedicated, passionate, generous, headline-grabbing, community-minded, political gadfly; yes, all these and more wrapped into one purveyor of ever-popular sweet potato pies and barbeque. While no one ever questioned Say McIntosh’s dedication to the people and community that he was a strident advocate for, it was also clear that the tactics and behavior that he exhibited in that advocacy ultimately served to his detriment, both personally, politically, and in his business.

Robert Robinson McIntosh was born in Osceola on January 16, 1943 as the fifth child in a family of eleven. When he was six, his family moved to Little Rock to live in the Granite Mountain area. His father often worked two or three jobs to provide for his family and was able to provide a home for his family even in an age of Jim Crow segregation. McIntosh once recalled an incident that occurred when his father worked at a Little Rock Kroger store when he was in the first grade. A customer addressed him as “boy,” and McIntosh recalled his father’s reaction: “My father looked at him — he was 40 years old; I never will forget it — and he said: ‘I’m 40 years old. How old do you have to be before you’re a man?’ McIntosh said. “That’s when my father was working at Kroger, and [the man] called my father ‘Mr. McIntosh’ from that day on.”1 His father instilled in him two traits, according to his brother Tommy: that it was always right to stand up for yourself if you wanted respect, and a strong work ethic. He would also add a strong aversion to injustice to those traits, with an equally strong willingness to act on them.

He attended segregated Horace Mann High School but dropped out in the tenth grade in 1958. He worked a series of jobs, settling on the restaurant industry as a place to build his skills. His first job in the industry was as a waiter at the original Franke’s Cafeteria in downtown Little Rock. From there, he put his entrepreneurial drive to work to eventually go into business for himself, specializing in his soon-to-be famous barbeque, home cooking, and sweet potato pies. His pies were what attracted a large and faithful community following and allowed him a large degree of prosperity in an age when black-owned businesses were truly coming into their own. His strong sense of community and concern for the less fortunate in impoverished black neighborhoods propelled him into a desire to give back to these same communities, which he would carry with him throughout his life. McIntosh first made news in 1976 by holding a free Thanksgiving Day dinner for poverty-stricken residents of Little Rock. That same year, he began his work as the city’s self-styled “Black Santa,” distributing toys to children whose families could not afford to provide them. The effort would endear him to the public but would also cause him financial distress that he would deal with for years. Yet he would be named as Arkansan of the Year, and Governor David Pryor proclaimed December 24, 1976 as “Say McIntosh Day” in Arkansas.

He was believed to have earned the nickname “Say” for being always willing to speak his mind or say something that was important to him and his community. In 1977, the first of McIntosh’s political protests occurred at the offices of the Alcoholic Beverage Control Board in Little Rock where he dumped a load of beer and whiskey bottles in objection of liquor permits being awarded business near his restaurant. In September 1979, he brought a truckload of farm animals to downtown Little Rock’s Metrocentre Mall to protest littering there and threatened to set 500 chickens loose there as well. The next month, he barged into Prosecuting Attorney Lee Munson’s office, turned over his desk, and assaulted Munson because he felt charges filed against him in connection with the Metrocentre incident were unjust. McIntosh was acquitted in Circuit Court. In January 1980, he interrupted a celebration of Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday at the Capitol by yelling at the participants, telling them to get back to work. That summer, he took his protest outside Little Rock by arriving at Fort Chaffee to object to the housing of Cuban refugees there, only then offer to feed the Cubans before being turned away by guards.2

The attention he had attracted inspired him to try his hand at elective politics. He filed as a candidate in the Democratic Primary for Lieutenant Governor in 1980 and joined a field of seven for the open seat. He made his platform one as promoting an example of a strong work ethic and cleaning up Arkansas. At rallies, he distributed sweet potato pie and lemonade to attendees, and often appeared with a broom as a prop. His chief attention-getter was an attempt walk from Little Rock to West Memphis pushing a wheelbarrow containing a towel and a Bible under the banner, “Praying and Working for a Better Arkansas.” He said that his trip was intend to encourage citizens to work and trust God, but emphasizing that his belief that God helps those who helps themselves, saying, “He won’t push the wheelbarrow for you.”3 Unusually warm temperatures and rain forced McIntosh to call off the walk after a few miles. He ran a respectable fourth in the primary with 12 percent of the vote and second in his home county of Pulaski, just behind the statewide winner, Winston Bryant.

The 1980s proved to be the height of McIntosh’s more outlandish political protests. In the fall of 1980, he joined the Republican Party and the Black Republican Caucus, serving as Vice-Chairman. Yet his relations with newly elected Republican Governor Frank White were poor, as McIntosh constantly attacked White for ignoring the council and him in particular. In the summer of 1981, he put himself up on a faux cross in front of the Capitol dressed in thermal underwear in the near 100-degree heat. His friends took him down as he began to suffer heat stroke. A few days later, he resigned from the BRC and staged the same ritual in front of the Governor’s Mansion while White met with foreign dignitaries inside. When one of the visitors asked why McIntosh was hanging on a cross, White replied in a deadpan tone, “He displeased me.” McIntosh did the cross stunt once more in protest of conditions at the Pulaski County Jail in 1983, but when Sheriff Tommy Robinson emerged with a chain saw, McIntosh promptly came down. His protests in subsequent years targeted conditions in prisons, cleaning up poor neighborhoods, burning the United States flag, and public drunkenness. He set up a field of wooden crosses to protest the growing numbers of victims of gang violence. He chopped down a tree meant to honor Dr. Martin Luther King because “blacks were not involved in the political process in Little Rock.”4 Initially a supporter of Governor Bill Clinton, he turned on him and had announced that he would run against Clinton and Former Governor Orval Faubus in the 1986 Democratic Gubernatorial Primary, but left without fling as another black candidate, W. Dean Goldsby, filed instead. McIntosh made one more attempt at elective office, unsuccessfully seeking a seat on the Little Rock City Board of Directors in 1988.

The height of McIntosh’s outlandish protests came in 1990 when he first attempted to welcome the Ku Klux Klan to Arkansas by offering to feed them barbeque. During the Republican Primary runoff for Lieutenant Governor in June, McIntosh arrived at a Little Rock television station and on live television assaulted Ralph Forbes, a former member of the American Nazi Party and candidate for that office. Forbes had prevented McIntosh from burning an American flag in front of the Capitol the previous Spring. When John Robert Starr, Managing Editor of the Arkansas Democrat, referred to him as “McIntrash,” McIntosh confronted the editor and forcibly crammed a copy of the paper in his mouth. During the 1992 presidential campaign, he distributed flyers accusing Clinton of fathering a black son out of wedlock. In 1992, his friend Senator Jerry Jewell, serving as Acting Governor in Governor Jim Guy Tucker’s absence pardoned his son, Tommy, who was serving time on a drug charge. He attacked a CNN producer in front of the federal courthouse in 1996 in order to interrupt the network’s report on the sentencing of Tucker.

McIntosh was increasingly beset by multiple financial and health issues as well as legal problems, and gradually faded from the scene in the 1990s. In 2011, the Department of Arkansas Heritage began the annual “Say it Ain’t Say’s Sweet Potato Pie Contest” at the Mosaic Templars’ Cultural Center in his honor. The event, along with its association with McIntosh, highlights an important holiday tradition in the black community. While his antics in the past were believed to have limited his impact, he said that hde hoped that his legacy would be, “What I was trying to do is get black people to stand up. That’s what it was all about.”5

1. David Koon, “Say McIntosh: The lion in winter.” Arkansas Times, October 5, 2011.

2. David Koon, “The Says of Our Lives.” Arkansas Times, October 5, 2011.

3. “McIntosh Begins Trek; His Goal is W. Memphis.” Arkansas Gazette, April 3, 1980.

4. Danny Russell, “Robert "Say" McIntosh (1943–).” Encyclopedia of Arkansas https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/robert-say-mcintosh-4225/ (Last Updated July 26, 2014)

5. Russell, “Robert "Say" McIntosh (1943–).”